Sexual Wellbeing Hub

The healthcare provider plays a key role in routinely and systematically bringing up and addressing sexual function and sexual concerns in prostate cancer survivorship

Let's talk about sex

For men who have been treated for prostate cancer, it's the sexual side-effects that are talked about the most when quality of life is considered.

94% of men on hormone therapy, such as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) experience erectile dysfunction (ED). This is linked to reduced sexual pleasure, penile shrinkage, weight gain, fatigue, and infertility. Men and their partners consistently report that these side-effects cause distress and disrupt their relationships.

One patient described erectile dysfunction as:

"One of the biggest challenges to a man. My wife and I had a healthy sex life before the operation and although it is not the be all and end all of our marriage, it played a big part. After 8 weeks post-operation and no movement in my penis, it is such a hard thing to deal with physically and mentally."

What's the reality for men experiencing side-effects?

Despite recommendations in numerous publications that assistance for sexual issues should be made readily available, men and their partners continue to receive little to no support. Discussions about sexual side-effects are still being omitted from consultations and there is a lack of consensus amongst healthcare professionals (HCPs) about who should take responsibility for management of side-effects. The Life After Prostate Cancer Study found that only 44% of all prostate cancer patients reported being offered interventions or a referral to a specialist clinic after treatment, and this fell to just 18% among those on monotherapy ADT. Another patient stated:

"Since my operation to remove my prostate, I was given the all clear. However, I've found the lack of aftercare extremely disappointing. I've had no offer of counselling from my GP or the hospital, and no explanation of what's next"

Our recommendation

- Sexual wellbeing support must be included in a patient's treatment and care plan/cancer review plan to support maintaining/or improving a good quality of life.

- HCPs need to be more transparent about the psychosexual effects and impact of prostate cancer treatment.

- HCPs should help manage expectations and ensure appropriate support is in place for men.

Our aim for this content is to raise awareness of this issue and to empower HCPs to:

- Provide better sexual wellbeing support to patients by sharing what the common sexual side-effects of prostate cancer and its treatment are.

- Recognise when/how you should talk to men diagnosed with prostate cancer about their sexual wellbeing pre and post treatment.

Further support

For a more in depth look into this topic, the Movember Guidelines are an excellent evidence and expert opinion-based framework designed to help clinicians assess and manage the sexual side-effects of prostate cancer therapies, and facilitate shared decision-making between clinicians, patients and partners.

Who should be having these conversations?

Since the prostate is a sexual organ, where treatment will inevitably impact sexual function and wellbeing, the topic should really be included in conversation with patients throughout the prostate cancer pathway, by everyone involved. Therefore, there is a responsibility to communicate what is going to happen sexually and reproductively both before, during, and after treatment. The amount of detail you go into may vary per role, but, ultimately, it is important that sexual wellbeing is not being missed in conversation with prostate cancer patients, and that they are referred on to specialist services when necessary.

You should be asking about this area of care in your Holistic Needs Assessment (HNA), following through with advice and support and it can also be raised during Cancer Care Reviews.

Guide your conversations by knowing the side-effects

There are a number of long-term side-effects that your patient may experience as a result of their prostate cancer treatment. The table below drawn from Table 2 in the Movember Guidelines provides a summary of the long-term sexual side-effects of prostate cancer and its treatment. This can be used as a foundation to initiate and guide your conversations.

We’ve included other side-effects of treatment as they may still impact patient sexual wellbeing e.g. bowel dysfunction is something to consider for patients who enjoy anal intercourse.

By knowing what these side-effects are, it can be used as an opener for conversations with your patient, to identify which, if any of the below, they may be experiencing.

Treatment type |

Long-term effects |

|

Surgery (radical prostatectomy; open, laparoscopic, robotic-assisted) |

Urinary dysfunction:

Sexual dysfunction:

|

|

Radiation (external beam or brachytherapy) |

Urinary dysfunction:

Sexual dysfunction:

Bowel dysfunction:

|

|

Hormone therapy (androgen deprivation therapy) |

Sexual dysfunction:

Other:

|

|

Expectant management (watchful waiting or active surveillance) |

|

When should I speak to my patient?

Research has shown that men and their partners are unlikely to initiate discussions on the side-effects of prostate cancer treatment on sexual function. So, it’s crucial as a healthcare professional that you are proactive and talk about this, even if you may feel embarrassed, uncomfortable or feel like it’s not your role.

The more this important conversation is normalised and becomes a part of your routine, the easier this will become. Your patient will thank you for having the conversation and it will improve their quality of life and prevent stress, embarrassment and isolation. Remember you are the healthcare professional in the room!

Pre and post treatment conversations

When should sexual wellbeing be discussed?

Prostate cancer patient sexual wellbeing should be brought into conversation early on following diagnosis and especially when treatment is first mentioned. Treatment will inevitably impact sexual function and likely overall sexual wellbeing and should therefore be well integrated in the pathway and included in conversation around regular check-ups.

Things to consider when having a conversation with your patient

It’s an overwhelming time for men who have been diagnosed and are about to be treated for their prostate cancer. Therefore, it’s critical that they receive the right care, advice and reassurances both pre and post treatment. This is where your role as a healthcare professional is key. What you say and what you do at these stages, will help men emotionally, psychologically and physically with their recovery and to deal with their side-effects.

There are specific needs to take into account when thinking about talking to your patient about potential side effects and how these may influence what you think, say and do.

In beginning to understand men’s needs, remember to:

- Be open.

- Promote inclusive language.

- Be aware of how protected characteristics (age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage/civil partnership, pregnancy/maternity, race, religion/belief, sex, sexual orientation) will influence conversations.

We’ve provided the below, found in the Movember Guidelines, as needs to consider when having this conversation.

Relationships: Men may be single, monogamous, widowed or have multiple partners. Relationship status shouldn’t be a barrier for input.

Age: Consider younger men and the impact on their fertility and the impact a diagnosis may have on older men that may want to continue having an active sex life and/or father children.

Type of sex: Men will have anal sex, man on man sex, use sex toys, non-penetrative sex.

Ethnicity and culture: Depending on a man’s culture and ethnicity there will be a variation in dealing with sexual matters, e.g. herbal remedies, perceptions of sexual dysfunction and masculinity. If you don’t know, then it’s okay to ask.

Sexuality: People identify in different ways, e.g. asexual, bisexual, heterosexual, gay, gender neutral, trans woman so it’s important to understand their specific needs and to avoid making assumptions.

Assessing your patient’s needs

There are three factors below that you should incorporate into your practice, when assessing your patients and their partners’ sexual wellbeing concerns before treatment.

-

Information on side-effects

Communicate: Talk to your patient about the sexual side-effects and ensure you maintain communication. -

Information on impact

Be realistic: Promote realistic expectations about how their specific treatment will impact their sexual function and wellbeing, their partner’s sexual experience and their sexual relationship/s. -

Information on management

Empower men:Reassure and let men and their partner/s know that there are biopsychosocial treatments for sexual issues that can mitigate sexual dysfunctions and improve sexual wellbeing which can lead to either the recovery or introduction of sexual intimacy e.g., using pumps pre-treatment to improve the health of tissue and improve blood flow through the penis, particularly if penile health is already poor, as well as pelvic floor exercises, etc.

Develop your skills

We know that this might be a difficult topic to broach with your patient, so we’ve compiled some prompts and top tips after speaking with our Sexual Support Service specialist nurses, as well as other HCPs in the field.

This includes what language and wording you may want to use to start developing these conversations. It should also give you the confidence to make referrals when necessary to someone or somewhere that can help your patient’s unique needs.

There is further information within the Movember Guidelines if you want to read more about this.

We know that this might be a difficult topic to approach with your patient, so we’ve put this guide together that gives Health Care Practitioners support on how to broach this subject with your patients, along with tips, phrases and things to consider. This has been compiled in consultation with our Sexual Support Service specialist nurses, as well as other expert healthcare professionals in the field.

Assessment framework

Research conducted by Queens University, Belfast in 2020, developed a conceptual communication framework EASSi. The framework emphasises routine engagement to normalise sexual concerns, brief, nonsensitive assessment, personalised advice based on treatment and relationship status, and a mechanism for referral to additional support or self-management resources in the form of a patient and partner handout.

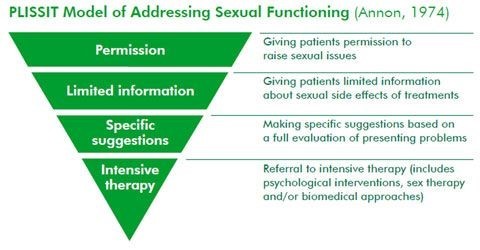

For example, the PLISSIT model below:

This model can be used to determine the different levels of intervention for individual patients.

Your approach

There is no “one size fits all” approach when talking about this subject matter with your patient. You will find that some men will talk about their sexual health easily and openly, whilst others will require a prompt. Some men might be desperate to get an erection back, whilst other men may be happy to wait and see what happens after treatment. Each patient (and partner/s) will have unique needs.

The below are points to consider when preparing and planning your conversation:

- Make it an open-topic conversation – bring it into conversation when you first start discussing treatment, and continue to bring the conversation up when you are following up on your patient’s care.

- Try and include your patient’s partner/s in appointments as much as possible. It’s easy for partner/s to feel isolated in this space when they will very like be affected by these issues too.

- If you are confident and relaxed around the conversation, then your patient is more likely to be too.

- By asking frank and honest questions it will help to create a safe and open environment to talk in.

- It’s fine to have a sense of humour around the subject to ease any embarrassment (laughing with not at of course when it’s appropriate).

- Show a willingness to listen and take an interest.

- Gauge your patient and let the conversation happen organically.

- Remember, try not to be presumptuous about people’s sex lives – it could look like anything.

- Provide clear and open communication.

- If you don’t know the answers, you can find them out later and let them know.

- If you feel outside your comfort zone or out of your depth, you can always refer on to someone who does - like a psychosexual support service or our sexual support line. The important thing is that this aspect of patient health is not ignored.

Reassurance

Providing reassurance to men is important as this will help to manage any anxiety and stress they may be feeling. The below are some phrases that you can use to do this.

- It’s still possible for you to have a satisfying sex life post-treatment. Would you like to speak to a specialist about this and find out more about what you can do?

- Yes, your sex life will be different, but according to some patients it got better than it was before, when they started exploring other ways to be intimate.

- It’s still possible to orgasm even without an erection, with practice, patience, and adaption.

Key phrases for starting the conversation

Whether you’re a HCP in a primary or secondary care setting, make every appointment you have with your patient count, and have a conversation about this subject with them.

It’s important to take into consideration your patient’s literacy levels and adapt your language accordingly. Consider using simple, adaptable language rather than possible technical. E.g., ‘you probably will no longer be able to ejaculate’ may be better understood if ‘ejaculate’ is replaced with ‘cum’.

Helpful phrases

We’ve put together some key phrases that other HCPs have used in having conversations with their patients.

- We know that problems with sexual function following prostate cancer treatment are very common with men. How has this affected you?

- We know having a diagnosis of prostate cancer can affect your sex life/sexual wellbeing. Is this something that’s affecting you at the moment? Please let me know if at any point I/we can be of help.

- We know that following treatment, men will experience side-effects, which includes erectile dysfunction, loss of libido, problems with ejaculating. How are things for you at the moment? For example, with getting an erection, masturbating, feeling like you want to be intimate with someone?

- There are many side effects for men after their treatment, one of which is to do with getting an erection. Is this something that’s been bothering you?

- Many men post treatment experience issues with closeness/intimacy/getting an erection. Is this something that’s affecting you? Please feel free to come and ask us.

- Is there anything that’s been on your mind, that you need some advice or help with? In terms of your sexual wellbeing?

- How’s your sex life doing?

- How are things – how’s your intimate/sex life?

Some men will benefit from receiving psychosexual support. Find out what services are available in your area and also consider providing men with the resources below. Also consider conducting a baseline assessment with your patient.

For example, you could say:

"The treatment that you’ve had has caused some big changes for you, and psychosexual support can help you manage and adapt to these changes. Is this something that you’d be interested in?"

The following links may be helpful in referring your patients:

Possible resources

Current NHS psychosexual support services:

You can also let your patient know about our own Sexual Support Service, which is run by our fantastic team of Specialist Nurses. Our specially trained nurses will be able to talk to patients about the impact of treatment on their sexual wellbeing and discuss the ways to manage such changes.

Please note that only the person wishing to use the service should complete this form.

Sexual function and wellbeing treatment and care management options

The idea of fixing sexual function can lead to disappointment, which is why we instead recommend focussing on adaption and how to manage the sexual side-effects.

We’ve provided an overview of the different ways on how to support your patient’s sexual function and wellbeing and this can be found below. There are additional web links to support services, products, information, and blogs, that you may want to inform your patients with.

Penile rehabilitation plays a significant role in helping to improve prostate cancer patients’ sex lives. This is achieved by increasing blood flow to the penis.

Physical support

- Pelvic floor exercises for the penis – these are just another form of physiotherapy. Physiotherapy for the penis should be normalised.

- Penis pumps – another form of physiotherapy for the penis, which patients can order. The most common pump used in the NHS is iMedicare, which you can direct men to and they can get it on prescription.

Medication and procedures

- MUSE – medicated pellets about the size of a grain of rice that is inserted into the urethra through the opening tip of the penis to help stimulate blood flow to the penis.

- Injections – another effective tool to achieve an erection if the man feels that achieving an erection is really important to improve their sexual wellbeing.

- Penile implants.

- PDE5 inhibitors. These are:

-

- Sildenafil (Viagra®) (lasts approx. 4 hours)

- The recommended staring dose is 50mg, but can be increased to 100mg if needed. It should be taken about an hour before planned sexual activity.

- Tadalafil (Cialis®) (lasts approx. 36 hours)

- The recommended starting dose is one 10 mg tablet before sexual activity. If the effect of this dose is too weak your doctor may increase the dose to 20 mg. You may take a CIALIS tablet at least 30 minutes before sexual activity. CIALIS may still be effective up to 36 hours after taking the tablet.

- You can also get a daily dose of 5mg which can be especially useful for penile rehabilitation, but difficult to get prescribed on the NHS.

- Tadafil is now off of the restricted list. This inhibitor is very important for men on ADT and works as a daily treatment.

- Vardenafil (Levitra®) (lasts approx. 4 -6 hours)

- The recommended dose is 10 mg taken as needed approximately 25 to 60 minutes before sexual activity. Based on efficacy and tolerability the dose may be increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg. The maximum recommended dose is 20 mg. The maximum recommended dosing frequency is once per day. Levitra can be taken with or without food. The onset of activity may be delayed if taken with a high fat meal

- Avanafil (Spedra®) 50mg, 100mg and 200mg.

- The recommended starting dose is 100 mg, taken as needed and on an empty stomach, approximately 15 to 30 minutes before sexual activity. Half-life of 6-17 hours

- Sildenafil (Viagra®) (lasts approx. 4 hours)

Adaptations

Sex toys – we know that sex toys can really help prostate cancer patients with their sex lives by adapting to new ways of having sex. A company specialising in sex toys have reached out to us to share some of the different types of sex toys that can be used to help support patients with their sex lives. These are:

- Hollow strap-ons.

- Tenga eggs.

- Male vibrators.

- Pumps.

- Rings.

Changing foreplay and having sex in the shower can also help with any issues with leaking and increase sensation.

Individual funding requests can be made to receive something on prescription that may not be on a specific area’s prescription list e.g. penis pumps.

Sexual support services

- Psychosexual support, erectile dysfunction clinics, or our Sexual Support Service, which is there to help patients as well as partners to talk through the impact of treatment on their sex life and about the options on how to deal with these changes.

- Our health information pages on sex and relationships

- Our sex and relationships online forum

- Recovering Man’s blog – a blog by a prostate cancer survivor who goes into detail about the ways in which treatment affected his sexual wellbeing.

You may also want to emphasise the importance of maintaining communication and intimacy with the patient’s partner, as this is vital for sustaining a relationship with these challenges.

Other resources

For a more in-depth framework please view the Movember Guidelines on how to best assess and manage the sexual side-effects of prostate cancer treatment.

Thank you

A heartfelt thank you to the men and loved ones who have highlighted key issues in the field so that we can help support change.

A grateful thank you to Will Kinnaird, Lorraine Grover, and Sophie Smith for providing their invaluable expertise on prostate cancer and sexual function and wellbeing throughout the project.

And a final thank you to the members of our Clinical Advisory Group for their insightful feedback to help ensure that this content is as useful as possible for fellow healthcare professionals, to ultimately benefit patients and their partners.

If you have any feedback on this content, please do not hesitate to get in touch via email: [email protected]

- Baratedi W.M., Tshiamo W.B., Mogobe K.D., McFarland D.M. (2020), Barriers to Prostate Cancer Screening by Men in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Integrated Review, J Nurs Scholarsh, 52:1, pp. 85-94

- Barocas D.A., Alvarez J., Resnick M.J, et al (2017), Association Between Radiation Therapy, Surgery, or Observation for Localized Prostate Cancer and Patient-Reported Outcomes After 3 Years, JAMA, 317:11, pp. 1126-1140

- Downing A, Wright P, Hounsome L, et al. Quality of life in men living with advanced and localised prostate cancer in the UK: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019

- Donovan K.A., Gonzalez B.D., Nelson A.M., Fishman M.N., Zachariah B., Jacobsen P.B. (2018), Effect of androgen deprivation therapy on sexual function and bother in men with prostate cancer: A controlled comparison, Psycho-Oncology, 27:1, pp. 316-324

- Hedestig O., Sandman P.O., Tomic R., Widmark A. (2005), Living after radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: a qualitative analysis of patient narratives, Acta Oncologica, 44:7, pp. 679-86

- Katz A. (2007), Quality of life for men with prostate cancer, Cancer Nursing, 30:4, pp. 302-308

- Kinnaird W. et al. (2020), The management of sexual dysfunction resulting from radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy to treat prostate cancer: A comparison of uro-oncology practice according to disease stage, International Journal of Clinical Practice

- Kushnir T., Gofrit O.N., Elkayam R., et al. (2016) Impact of Androgen Deprivation Therapy on Sexual and Hormonal Function in Patients Receiving Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Israel Medical Association Journal, 18:1, pp. 49-53.

- Mellor R.M., Greenfield S.M., Dowswell G., Sheppard J.P., Quinn T. and McManus R.J. (2013), Health Care Professionals’ Views on Discussing Sexual Wellbeing with Patient Who Have Had a Stroke: A Qualitative Study, PLoS One, 8: 10

- Perz J., Ussher J.M., Gilbert E. (2013), Constructions of sex and intimacy after cancer: Q methodology study of people with cancer, their partners, and health professionals. BMC Cancer, 13:270

- Rosser B.R., Capistrant B., Torres B., et al. (2016), The Effects of Radical Prostatectomy on Gay and Bisexual Men’s Mental Health, Sexual Identity and Relationships: Qualitative Results from the Restore Study, Sexual & Relationship Therapy, 31:4, pp. 446-461

- Sanders S., Pedro L.W., Bantum E.O., Galbraith M.E. (2006), Couples surviving prostate cancer: Long-term intimacy needs and concerns following treatment, Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 10:4, pp. 503-8

- Simon Rosser B.R., Merengwa E., Capistrant B.D., et al. () Prostate Cancer in Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Review, LGBT Health, 3:1, pp. 32-41

- Skolarus T.A., Wolf A.M., Erb N.L., et al. (2014), American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines, CA Cancer J Clin, 64:4, pp. 225-49

- Tanner T., Galbraith M., Hays L. (2011), From a Woman’s Perspective: Life as a Partner of a Prostate Cancer Survivor. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 56:2, pp. 154-160.

- Ussher J.M., Perz J., Kellett A., et al. (2016), Health-Related Quality of Life, Psychological Distress, and Sexual Changes Following Prostate Cancer: A Comparison of Gay and Bisexual Men With Heterosexual Men, The journal of sexual medicine, 13:3, pp. 425-34

- Wittmann D., Carolan M., Given B., et al. (2015), What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: Toward the development of a conceptual model of couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer, Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12:2, pp. 494-504