Permanent seed brachytherapy

Improving our information

This webpage is due to be reviewed shortly. To make sure it as accurate and accessible we want to hear your thoughts by completing a short survey on what you have read today. It should take no longer than three minutes.

What is permanent seed brachytherapy?

Permanent seed brachytherapy, also known as low dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy, is a type of radiotherapy where tiny radioactive seeds are put into your prostate. Each radioactive seed is the size and shape of a grain of rice. The seeds stay in the prostate forever and give a steady dose of radiation over a few months.

The radiation damages the prostate cells and stops them dividing and growing. The cancer cells can't recover from this damage and die. But healthy cells can repair themselves more easily.

The seeds release most of their radiation in the first three months after they’re put into the prostate. After around 8 to 10 months, almost all the radiation has been released. The amount of radiation left in the seeds is so small that it doesn’t have an effect on your body.

Permanent seed brachytherapy is as good at treating localised prostate cancer that has a low risk of spreading as surgery (radical prostatectomy) or external beam radiotherapy. Read more about other treatment options for localised prostate cancer.

Permanent seed brachytherapy fact sheet

This fact sheet is for anyone who is thinking about having permanent seed brachytherapy to treat their prostate cancer.

Who can have permanent seed brachytherapy?

Permanent seed brachytherapy on its own may be suitable for men whose hasn't spread outside the prostate (localised prostate cancer). This is because the radiation from the radioactive seeds doesn’t travel very far, so will only treat cancer that is still inside the prostate.

You may be able to have brachytherapy together with external beam radiotherapy if you have localised or locally advanced prostate cancer. This is sometimes called a brachytherapy boost. You may also have hormone therapy alongside your external beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy boost. Having these other treatments at the same time as permanent seed brachytherapy can help make the treatment more effective. But it can also increase the risk of side effects.

If you have localised or locally advanced prostate cancer, your Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG) will help your doctor decide what treatment options are suitable for you. However, some doctors may use the old system of low, intermediate and high risk instead. You can read more in our booklet, Prostate cancer: A guide for men who’ve just been diagnosed.

When is permanent seed brachytherapy not suitable?

Permanent seed brachytherapy on its own won’t be suitable if your cancer has spread just outside your prostate (locally advanced prostate cancer ). But, if you have locally advanced prostate cancer, you may be offered brachytherapy together with external beam radiotherapy (see above).

You won't be able to have permanent seed brachytherapy at all if your cancer has spread to other parts of your body (advanced prostate cancer).

It may not be suitable if you have a very large prostate. If you do have a large prostate you may be able to have hormone therapy before treatment to shrink your prostate.

It may also not be suitable if you have severe problems urinating, such as those caused by an enlarged prostate or overactive bladder. These include needing to urinate more often, a weak urine flow or problems emptying your bladder. Permanent seed brachytherapy can make these problems worse. Before you have treatment, your doctor, nurse or radiographer will ask you about any urinary problems, and you may have some tests.

You may not be able to have permanent seed brachytherapy if you have some types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This is because it could make your bowel problems worse. Brachytherapy won’t be suitable if you’ve had surgery to remove your rectum (back passage), because the treatment involves using an ultrasound probe in the back passage to make sure the seeds are put in the correct place. Your doctor or nurse will explain your treatment options to you.

If you’ve recently had surgery to treat an enlarged prostate, called a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), you may have to wait atleast three months before having permanent seed brachytherapy. Some hospitals don’t offer brachytherapy to men who’ve had a TURP because it can make the treatment more difficult to perform.

You will usually have a general anaesthetic while the brachytherapy seeds are put in place, so you’ll be asleep and won’t feel anything. This means permanent seed brachytherapy may only be an option if you are fit and healthy enough to have an anaesthetic. However, you may be able to have a spinal (epidural) anaesthetic instead. This may depend on what your hospital offers.

Not all hospitals offer permanent seed brachytherapy. If your hospital doesn’t do it, your doctor may refer you to one that does.

What are the advantages and disadvantages?

What may be important to one man might be less important to someone else. If you are offered permanent seed brachytherapy, speak to your doctor or nurse before deciding whether to have it. They will be able to help you think about which treatment option is right for you. There’s usually no rush to make a decision so give yourself time to think about whether permanent seed brachytherapy is right for you.

Advantages

- Recovery is quick, so most men can return to their normal activities one or two days after treatment.

- Permanent seed brachytherapy delivers radiation directly into the prostate, so there may be less damage to surrounding healthy tissue, and a lower risk of some side effects.

- You will only be in hospital for one or two days.

- If your cancer comes back, you may be able to have further treatment.

Disadvantages

- Permanent seed brachytherapy can cause side effects such as urinary and erection problems. It can also cause bowel problems but this isn't common.

- You will need a general or spinal anaesthetic, which can have side effects.

- It may be some time before you know whether the treatment has been successful.

- You will need to avoid sitting close to pregnant women or children during the first two months after treatment.

If you are having external beam radiotherapy or hormone therapy as well as permanent seed brachytherapy, think about the advantages and disadvantages of those treatments as well.

What does treatment involve?

You will be referred to a specialist who treats cancer with radiotherapy, called a clinical oncologist. The treatment itself may be planned and carried out by other specialists including a therapy radiographer, a radiologist, a urologist, a physicist and sometimes a specialist nurse.

Each hospital may do things slightly differently but you will usually have:

- an appointment to check the treatment is suitable for you

- a planning session, to plan the treatment

- the treatment itself.

You will have the treatment during one or two hospital visits. Many hospitals offer treatment in just one visit, where your treatment will be planned and the seeds put in at the same time under the same anaesthetic. This is sometimes called a one-stage procedure. You may not need to stay in hospital overnight.

If your treatment is spread over two visits, you will have a planning session on your first visit. The radioactive seeds will be put in on the second visit, two to four weeks later. You may hear this called a two-stage procedure. Some men may be offered the two-stage procedure, for example, if they need treatment to reduce the size of the prostate. Some hospitals only offer the two-stage procedure.

Before the planning session, let your specialist know if you are taking any medicines, especially medicines that thin your blood such as aspirin, warfarin or clopidogrel. Don’t stop taking any medicines without speaking to your doctor or nurse.

Planning session

During the planning session, you will have an ultrasound scan to find out the size, shape and position of your prostate. This is called a volume study and is done by a clinical oncologist, physicist, radiographer or radiologist. They will use the scan to work out how many radioactive seeds you need.

It’s important that your bowel is empty so the scan shows clear images of your prostate. You may need to take a medicine called a laxative the day before the planning session to empty your bowels. Or you might be given an enema when you arrive at the hospital instead. An enema is a liquid medicine that is put inside your back passage (rectum). Your doctor, nurse or radiographer will give you more information about this.

You will usually have a general anaesthetic so that you’re asleep during the ultrasound scan. This will be given by a health professional called an anaesthetist. If you can’t have a general anaesthetic for health reasons, you may be able to have a spinal (epidural) anaesthetic. This is where anaesthetic is injected into your spine so that you can’t feel anything in your lower body. In some hospitals, the anaesthetist will talk through the different types of anaesthetic before deciding with you which is the best option.

A thin tube (catheter) may be passed up your penis into your bladder to drain urine, and an ultrasound probe is put inside your back passage. The probe is attached to an ultrasound machine that displays an image of the prostate. Your doctor, radiographer or physicist will use this image to work out how many radioactive seeds you need and where to put them.

The planning session is a final check that the treatment is suitable for you. If the scan shows that your prostate is too large, you may be offered hormone therapy for up to six months to shrink your prostate. You’ll then have another planning session before you have the seeds put in. Very occasionally, the scan may show that permanent seed brachytherapy isn’t possible because of the position of your prostate within the pelvic bones. If this happens, your specialist will discuss other treatment options with you.

The planning session usually takes about half an hour plus the time it takes for you to recover from the anaesthetic. You can go home the same day if you aren’t having the treatment straight away. Ask a friend or family member to take you home, as you shouldn’t drive for 24 to 48 hours after an anaesthetic.

Placing the seeds

The clinical oncologist will put the seeds into your prostate. If you have the treatment on the same day as your planning session, the seeds will be put in straight after the planning scan, under the same anaesthetic.

If you have the treatment on a different day to your planning session, you’ll need another anaesthetic on the day of your treatment. You may also need to take another laxative, or have another enema to empty your bowels for the treatment. You'll usually have a catheter to drain urine from your bladder.

An ultrasound probe is again put inside your back passage to take images of your prostate and make sure the seeds are put in the right place. In some hospitals, the clinical oncologist might put gel into your urethra (the tube you urinate through). This is instead of a catheter and helps the doctor see your urethra more clearly so they avoid putting any seeds into it.

The clinical oncologist then puts thin needles through your perineum (the area between the testicles and the back passage), and into your prostate. They pass the radioactive seeds through the needles into the prostate. The needles are then taken out, leaving the seeds behind.

Depending on the size of your prostate, between 60 and 120 seeds are put into the prostate using around 15 to 30 needles. The seeds can be loose individual seeds or linked together in a chain using material that slowly dissolves. Each hospital is different and the clinical oncologist will decide what type of seeds you will have. Treatment usually takes 45 to 90 minutes.

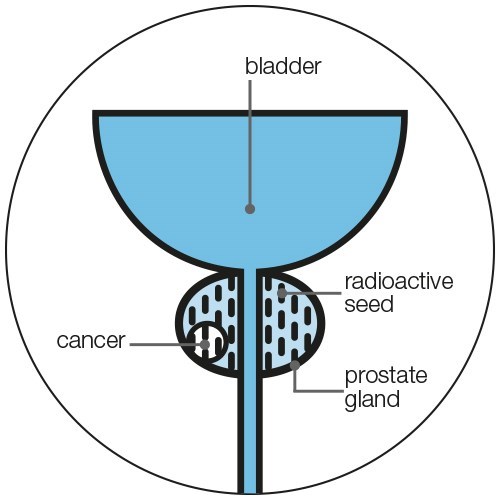

Where the seeds go in the prostate

After your treatment

You’ll wake up from the anaesthetic in the recovery room, before going back to the ward or discharge area. Most men feel fine after a general anaesthetic but a few men feel sick or dizzy. Your nurse may give you an ice pack to put between your legs to help prevent swelling.

If you have a catheter, it will usually be removed before you wake up but it may be left in for a few hours until you are fully awake. Very rarely, you might go home with your catheter and have to return within a few days to have it removed. Having the catheter removed may be uncomfortable, but it shouldn’t be painful.

You can go home when you’ve recovered from the anaesthetic and can pass urine. Most men go home on the same day as their treatment. But some men find it difficult to urinate at first, and need to stay in hospital overnight. You shouldn’t drive for 24 to 48 hours after the anaesthetic. Ask a family member or friend to take you home.

Your doctor or nurse will give you any medicines that you need at home. These may include drugs to help you urinate, such as tamsulosin, and antibiotics to prevent infection.

You may have some pain or bleeding from the area where the needles were put in. You can take pain-relieving drugs, such as paracetamol, for the first few days if you need to.

When to call your doctor, nurse or radiographer

Your doctor, nurse or radiographer will give you a telephone number to call if you have any questions or concerns. Contact them if any of the following things happen.

- If your urine is very bloody or has large clots in it, you may have some bleeding in your prostate. Contact your doctor or nurse as soon as possible.

- If you suddenly and painfully can’t urinate, you may have acute urine retention. Go to your local accident and emergency (A&E) department as this will need treatment as soon as possible. Take information about your cancer treatment with you, if you can.

- If you have a high temperature (more than 38ºC or 101ºF), this may be a sign of infection. Contact your doctor or nurse or go to your local A&E department.

What happens after permanent seed brachytherapy?

The prostate absorbs most of the radiation, and it’s safe for you to be near other people or pets. But you should avoid sitting closer than 50 cm (20 inches) to pregnant women and children during the first two months after treatment. You can give children a cuddle (at chest level) for a few minutes each day, but avoid having them on your lap. If you have pets, try not to let them sit on your lap for the first two months after treatment. Your doctor or nurse will talk to you about this in more detail.

Although the seeds usually stay in the prostate it is possible, but rare, for seeds to come out in your semen when you ejaculate. To be on the safe side, don’t have sex for a few days after treatment, and use a condom the first five times you ejaculate. Double-wrap used condoms and put them in the bin.

It is also rare for a seed to come out in your urine. If this happens at the hospital, don’t try to pick it up. Leave it where it is and let the hospital staff know straight away. If this happens after you’ve left the hospital, don’t try to pick up the seed. Just flush it down the toilet.

Always tell your doctor, nurse or radiographer if you think you have passed a seed. Your treatment will still work, because there will still be enough radiation left in the prostate to treat your cancer.

It is possible for a seed to move into your bloodstream and travel to another part of your body, but this is rare. This shouldn’t do any harm and will often be picked up when you have a scan at your follow-up appointment. If you have any unusual symptoms, speak to your doctor or nurse.

Your radiographer will give you an advice card that says you’ve had treatment with internal radiation. You should carry this card with you for at least 20 months after your treatment.

If a man dies, for whatever reason, in the first 20 months after having treatment, it won’t be possible to have a cremation because of the radioactive seeds. Speak to your doctor or nurse if you are worried about this. Some men decide not to have permanent seed brachytherapy because of this – for personal or religious reasons.

Going back to normal activities

You should be able to return to your normal activities in a few days. You can go back to work as soon as you feel able. This will depend on how much physical effort your work involves. It’s best to avoid heavy lifting for a few days after having the seeds put in. Speak to your doctor, nurse or radiographer about your own situation.

Travel

Remember to take your advice card with you when you travel. The radiation in the seeds can occasionally set off metal or radiation sensors at the airport, train station or cruise port.

Speak to your doctor, nurse or radiographer if you plan to travel anywhere soon after having permanent seed brachytherapy, or if you have any concerns about holidays and travel plans. Read more about travelling with prostate cancer.

Your follow-up appointment

You’ll have an appointment with your doctor, nurse or radiographer a few weeks after your treatment. They will check how well you are recovering, your PSA level, and ask about any side effects you might have.

After your treatment you’ll have a computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to check the position of the seeds. This can happen on the same day as your treatment, but it may be up to six weeks after your treatment, depending on your hospital.

PSA test

This is a blood test that measures the amount of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in your blood. PSA is a protein produced by normal cells in your prostate, and also by prostate cancer cells.

You will have regular PSA tests after your treatment to check how well it has worked. You will also be asked about any side effects. In most hospitals, you’ll have a PSA test after six weeks of your treatment. Then for the next two years you will have a PSA test at least every six months, and then at least once a year after that. Each hospital will do things slightly differently, so ask your doctor or nurse how often you will have PSA tests.

Your PSA should drop to its lowest level (nadir) 18 months to two years after treatment. How quickly this happens, and how low your PSA level falls, varies from man to man, and will depend on how big your prostate is and whether you’re also having hormone therapy. Your PSA level won’t fall to zero as your healthy prostate cells will continue to produce some PSA.

Your PSA level may rise after your treatment, and then fall again. This is called ‘PSA bounce’. It could happen up to three years after treatment. This is more common in younger men and men with a large prostate. It is normal, and doesn’t mean your cancer has come back or that you need more treatment.

If your PSA level consistently rises, particularly in a short amount of time, this could be a sign that cancer has come back. If this happens, your doctor will talk to you about further tests and treatment options if you need them. Further treatment options may include hormone therapy, HIFU, cryotherapy, or high dose-rate brachytherapy. Surgery might also be an option, but there's a higher risk of side effects if you've already had brachytherapy.

Read more about follow-up appointments and further treatment options.

What are the side effects?

Like all treatments, permanent seed brachytherapy can cause side effects. These will affect each man differently, and you may not get all the possible side effects.

Side effects usually start to appear about a week after treatment, when radiation from the seeds starts to have an effect. They are generally at their worst a few weeks or months after treatment, when the swelling is at its worst and the radiation dose is strongest. They are often worse in men with a large prostate, as more seeds and needles are used during their treatment. Side effects should improve over the following months as the seeds lose their radiation and the swelling goes down.

You might have worse side effects if you have permanent seed brachytherapy together with external beam radiotherapy and hormone therapy.

You might also get more side effects if you had problems before the treatment. For example, if you already had urinary, erection or bowel problems, these may get worse after permanent seed brachytherapy.

After the treatment, you might get some of the following:

- blood-stained urine or rusty or brown-coloured semen for a few days or weeks

- bruising and pain in the area between your testicles and back passage which can spread to your inner thighs and penis – this will disappear in a week or two

- discomfort when you urinate and a need to urinate more often, especially at night, and more urgently.

Some side effects may take several weeks to develop and may last for longer. These may include problems urinating, erection problems, bowel problems and tiredness. Sometimes long-term or late side effects after radiotherapy treatment are called pelvic radiation disease. The Pelvic Radiation Disease Association has more information.

Smoking

Researchers have been looking at whether smoking increases the chance of having long-term bowel and urinary problems after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. At the moment only a small number of studies have been done, so we need more research into this. If you’re thinking of stopping smoking there’s lots of information and support available on the NHS website.

Urinary problems

Permanent seed brachytherapy can irritate the bladder and urethra. You may hear this called radiation cystitis. Symptoms include:

- needing to urinate more often or urgently

- difficulty urinating

- discomfort or a burning feeling when you urinate

- blood in your urine.

In some men, permanent seed brachytherapy can cause the prostate to swell, narrowing the urethra and making it difficult to urinate.

A few men find they suddenly and painfully can’t urinate in the first few days or weeks after treatment. This is called acute urine retention. If this happens, contact your doctor or nurse straight away, or go to your nearest accident and emergency (A&E) department as soon as possible. They may need to put in a catheter to drain the urine. You may need to have the catheter in for several weeks until your symptoms have settled down.

Urinary problems may be worse in the first few weeks after brachytherapy, especially in men with a large prostate, but they usually start to improve after a few months.

Medicines called alpha-blockers may help with problems urinating. You can also help yourself by drinking liquid regularly (two litres or three to four pints a day) and by avoiding drinks that may irritate the bladder, such as alcohol, fizzy drinks, artificial sweeteners, and drinks with caffeine, such as tea and coffee.

Permanent seed brachytherapy can also cause scarring in your urethra, making it narrower over time. This is called a stricture, and can make it difficult to urinate. This is rare and may happen several months or years after treatment. If it happens, you might need an operation to widen your urethra or the opening of the bladder.

Some men leak urine (urinary incontinence) after permanent seed brachytherapy, but this isn’t common. It may be more likely if you’ve previously had surgery to treat an enlarged prostate, called a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Problems with leaking urine may improve with time, and there are ways to manage them.

Read more about urinary problems and how to manage them, or visit our interactive online guide for lots more tips.

Bowel problems

Your bowel and back passage are close to the prostate. Permanent seed brachytherapy can irritate the lining of the bowel and back passage, which can cause bowel problems. The risk of bowel problems after permanent seed brachytherapy is low. But you're more likely to have problems if you’re also having external beam radiotherapy.

Bowel problems can include:

- loose and watery bowel movements (diarrhoea)

- passing more wind than usual

- needing to empty your bowels more often

- needing to empty your bowels urgently

- bleeding from the back passage

- feeling that you need to empty your bowels but not being able to go.

Bowel problems tend to be mild and are less common than after external beam radiotherapy. They often get better with time but a few men have problems a few years after treatment. Try not to be embarrassed to tell your hospital doctor or your GP about any bowel problems. There are treatments that can help.

A small number of men may have bleeding from the back passage after brachytherapy. This can also be a sign of other problems such as piles (haemorrhoids) or more serious problems such as bowel cancer, so tell your nurse or GP about any bleeding. They may do tests to find out what is causing it. They can also tell you about treatments that can help.

Using a rectal spacer to protect your back passage

Your doctor may suggest using a rectal spacer to help protect the inside of your back passage from radiation damage. The spacer is placed between your prostate and your back passage. This means that less radiation reaches your back passage, which may help to lower your risk of bowel problems during or after your treatment.

Rectal spacers aren’t commonly used in permanent seed brachytherapy alone. But you may have one if you’re also having external beam radiotherapy. Rectal spacers are still new and aren’t very common yet, so they might not be available at your hospital. Ask your doctor, nurse or radiographer for more information about rectal spacers, their side effects and other ways to manage bowel problems.

Screening for bowel cancer

If you’re invited to take part in the NHS bowel screening programme soon after having brachytherapy, the test may pick up some blood in your bowel movements, even if you can’t see any blood yourself. Your doctor, nurse or radiographer may suggest that you delay your bowel screening test for a few months if you’ve recently had brachytherapy. This will help to make sure you don’t get incorrect results.

A small number of men get blood in their bowel movements after permanent seed brachytherapy, and this shouldn’t be anything to worry about. But if you notice blood, you should always let your doctor, nurse or radiographer know.

Sexual side effects

Brachytherapy can affect the blood vessels and nerves that control erections. This may cause problems getting or keeping an erection (erectile dysfunction). Erection problems may not happen straight after treatment, but sometimes develop some time afterwards.

The risk of long-term erection problems after brachytherapy varies from man to man. You may be more likely to have problems if you had any erection problems before treatment, or if you are also having hormone therapy or external beam radiotherapy.

If you have anal sex and prefer being the penetrative partner you normally need a strong erection, so erection problems can be a particular issue.

There are ways to manage erection problems, including treatments that may help keep your erection hard enough for anal sex. Ask your doctor or nurse about these, or speak to our Specialist Nurses.

You may produce less semen than before the treatment, or none at all. This can be a permanent side effect of brachytherapy. Your orgasms may feel different or you may get some pain in your penis when you orgasm. You may also notice a small amount of blood in the semen. This usually isn’t a problem, but tell your doctor or nurse if it happens. Some men have weaker orgasms than before treatment, and a small number of men can no longer orgasm afterwards.

If you have anal sex and are the receptive partner, there’s a risk that your partner might be exposed to some radiation during sex in the first few months after treatment. Anal sex or stimulation using fingers or sex toys is unlikely to move the brachytherapy seeds out of the prostate. Your doctor may suggest you avoid receiving anal sex or anal play for the first six months after your treatment. Ask your doctor for more information about having anal sex after permanent seed brachytherapy. They may contact the local medical physics team who can give specific information tailored to you.

If you prefer to be the receptive partner during anal sex, then bowel problems or a sensitive anus after permanent seed brachytherapy may affect your sex life. Even when the risk of radiation to your partner has passed, wait until any bowel problems have improved before trying anal play or sex.

Read more about sexual side effects after prostate cancer treatment. We also have specific information if you're a gay or bisexual man. And there are lots of tips for managing sexual problems in our interactive online guide.

Having children

Brachytherapy may make you infertile, which means you may not be able to have children naturally. But it may still be possible to make someone pregnant after brachytherapy.

It’s possible that the radiation could change your sperm and this might affect any children you conceive. The risk of this is very low, but use contraception for at least a year after treatment if there’s a chance you could get someone pregnant. Ask your doctor or nurse for more information.

If you plan to have children in the future, you may be able to store your sperm before you start treatment so that you can use it later for fertility treatment. If this is relevant to you, ask your doctor, nurse or radiographer whether sperm storage is available locally.

Tiredness (fatigue)

You may feel tired for the first few days after treatment as you recover from the anaesthetic. The effect of radiation on the body may make you feel tired for longer, especially if you’re also having external beam radiotherapy or hormone therapy. If you get up a lot during the night to urinate, this can also make you feel tired during the day.

Fatigue is extreme tiredness that can affect your everyday life. It can affect your energy levels, motivation and emotions. Fatigue can continue after the treatment has finished and may last several months.

There are things you can do to help manage fatigue. For example, planning your day to make the most of when you have more energy. Read more about fatigue, or get tips for dealing with fatigue in our interactive online guide. Our Specialist Nurses also offer support that can help you improve your fatigue over time.

Questions to ask your doctor, radiographer or nurse

- Will I have a planning session at a different time to the treatment, or immediately before?

- Will I have external beam radiotherapy or hormone therapy as well?

- What side effects might I get?

- How will we know if the treatment has worked?

- What should my PSA level be after treatment and how often will you test it?

- If my PSA continues to rise, what other treatments are available?

References

Updated: October 2022 | Due for Review: October 2025

• Allott EH, Masko EM, Freedland SJ. Obesity and Prostate Cancer: Weighing the Evidence. Eur Urol. 2013 May;63(5):800–9.

• Andreyev HJN. GI Consequences of Cancer Treatment: A Clinical Perspective. Radiat Res. 2016 Mar 28;185(4):341–8.

• Avellino G, Theva D, Oates RD. Common urologic diseases in older men and their treatment: how they impact fertility. Fertil Steril. 2017 Feb;107(2):305–11.

• Awad MA, Gaither TW, Osterberg EC, Murphy GP, Baradaran N, Breyer BN. Prostate cancer radiation and urethral strictures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018 Jun;21(2):168–74.

• Baker H, Wellman S, Lavender V. Functional Quality-of-Life Outcomes Reported by Men Treated for Localized Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016 Mar;43(2):199–218.

• Bourke L, Smith D, Steed L, Hooper R, Carter A, Catto J, et al. Exercise for Men with Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016 Apr;69(4):693–703.

• Bownes P, Coles I, Doggart A, Kehoe T. UK Guidance on Radiation Protection Issues following Permanent Iodine- 125 Seed Prostate Brachytherapy [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.ipem.ac.uk/ScientificJournalsPublications/UKGuidanceonRadiationProtectionIssuesfollowi.aspx

• Cao Y, Ma J. Body Mass Index, Prostate Cancer-Specific Mortality, and Biochemical Recurrence: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa). 2011 Jan 13;4(4):486–501.

• Chao MWT, Grimm P, Yaxley J, Jagavkar R, Ng M, Lawrentschuk N. Brachytherapy: state-of-the-art radiotherapy in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2015 Oct;116:80–8.

• Corey G, Yoosuf ABM, Workman G, Byrne M, Mitchell DM, Jain S. UK & Ireland Prostate Brachytherapy Practice Survey 2014-2016. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2018;10(3):238–45.

• Davies NJ, Batehup L, Thomas R. The role of diet and physical activity in breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivorship: a review of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2011 Nov 8;105:S52–73.

• Dempsey PJ. Creation of a protective space between the rectum and prostate prior to prostate radiotherapy using a hydrogel spacer. Clin Radiol. 2022;6.

• Discacciati A, Orsini N, Wolk A. Body mass index and incidence of localized and advanced prostate cancer--a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann Oncol. 2012 Jan 6;23(7):1665–71.

• Frazzoni L, La Marca M, Guido A, Morganti AG, Bazzoli F, Fuccio L. Pelvic radiation disease: Updates on treatment options. World J Clin Oncol. 2015 Dec 10;6(6):272–80.

• Gaither TW, Awad MA, Osterberg EC, Murphy GP, Allen IE, Chang A, et al. The Natural History of Erectile Dysfunction After Prostatic Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med. 2017 Sep 1;14(9):1071–8.

• Gardner JR, Livingston PM, Fraser SF. Effects of Exercise on Treatment-Related Adverse Effects for Patients With Prostate Cancer Receiving Androgen-Deprivation Therapy: A Systematic Review. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32(4):335–46.

• Gerdtsson A, Poon JB, Thorek DL, Mucci LA, Evans MJ, Scardino P, et al. Anthropometric Measures at Multiple Times Throughout Life and Prostate Cancer Diagnosis, Metastasis, and Death. Eur Urol. 2015 Dec;68(6):1076–82.

• Gianotten WL. Sexual aspects of shared decision making and prehabilitation in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Int J Impot Res. 2021 May;33(4):397–400.

• Hechtman LM. Clinical Naturopathic Medicine [Internet]. Harcourt Publishers Group (Australia); 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 21]. 1610 p. Available from: http://www.bookdepository.com/Clinical-Naturopathic-Medicine-Leah-Hechtman/9780729541923

• Henson CC, Burden S, Davidson SE, Lal S. Nutritional interventions for reducing gastrointestinal toxicity in adults undergoing radical pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2014 Nov 18];(11). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009896.pub2

• Ho T, Gerber L, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC, Kane CJ, et al. Obesity, Prostate-Specific Antigen Nadir, and Biochemical Recurrence After Radical Prostatectomy: Biology or Technique? Results from the SEARCH Database. Eur Urol. 2012 Nov;62(5):910–6.

• Hu MB, Xu H, Bai PD, Jiang HW, Ding Q. Obesity has multifaceted impact on biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of 36,927 patients. Med Oncol Northwood Lond Engl. 2014 Feb;31(2):829.

• Husson O, Mols F, Poll-Franse LV van de. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010 Sep 24;mdq413.

• Huyghe E, Delannes M, Wagner F, Delaunay B, Nohra J, Thoulouzan M, et al. Ejaculatory Function After Permanent 125I Prostate Brachytherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2009 May;74(1):126–32.

• Ishiyama H, Hirayama T, Jhaveri P, Satoh T, Paulino AC, Xu B, et al. Is There an Increase in Genitourinary Toxicity in Patients Treated With Transurethral Resection of the Prostate and Radiotherapy?: A Systematic Review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jun;37(3):297–304.

• Jassem J. Tobacco smoking after diagnosis of cancer: clinical aspects. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019 May;8(S1):S50–8.

• Keilani M, Hasenoehrl T, Baumann L, Ristl R, Schwarz M, Marhold M, et al. Effects of resistance exercise in prostate cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Jun 10;

• Keogh JWL, MacLeod RD. Body Composition, Physical Fitness, Functional Performance, Quality of Life, and Fatigue Benefits of Exercise for Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 Jan;43(1):96–110.

• Keto CJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC, Kane CJ, Amling CL, et al. Obesity is associated with castration-resistant disease and metastasis in men treated with androgen deprivation therapy after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. BJU Int. 2011;110(4):492–8.

• King MT, Keyes M, Frank SJ, Crook JM, Butler WM, Rossi PJ, et al. Low dose rate brachytherapy for primary treatment of localized prostate cancer: A systemic review and executive summary of an evidence-based consensus statement. Brachytherapy. 2021 Nov;20(6):1114–29.

• Kishan A, Kupelian P. Late rectal toxicity after low-dose-rate brachytherapy: incidence, predictors, and management of side effects. Brachytherapy. 2014;14(2):148–59.

• Kubo K, Wadasaki K, Kimura T, Murakami Y, Kajiwara M, Teishima J, et al. Clinical features of prostate-specific antigen bounce after 125I brachytherapy for prostate cancer. J Radiat Res (Tokyo). 2018 Sep 1;59(5):649–55.

• Lardas M, Liew M, van den Bergh RC, De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Van den Broeck T, et al. Quality of Life Outcomes after Primary Treatment for Clinically Localised Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur Urol. 2017 Dec;72(6):869–85.

• Larkin D, Lopez V, Aromataris E. Managing cancer-related fatigue in men with prostate cancer: A systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions. Int J Nurs Pract. 2014 Oct;20(5):549–60.

• Lehto US, Tenhola H, Taari K, Aromaa A. Patients’ perceptions of the negative effects following different prostate cancer treatments and the impact on psychological well-being: a nationwide survey. Br J Cancer. 2017 Mar;116(7):864–73.

• Lin PH, Aronson W, Freedland SJ. Nutrition, dietary interventions and prostate cancer: the latest evidence. BMC Med. 2015 Jan 8;13:3.

• Maletzki P, Schwab C, Markart P, Engeler D, Schiefer J, Plasswilm L, et al. Late seed migration after prostate brachytherapy with Iod-125 permanent implants. Prostate Int. 2018 Jun;6(2):66–70.

• McInnis MK, Pukall CF. Sex After Prostate Cancer in Gay and Bisexual Men: A Review of the Literature. Sex Med Rev. 2020 Jul;8(3):466–72.

• Menichetti J, Villa S, Magnani T, Avuzzi B, Bosetti D, Marenghi C, et al. Lifestyle interventions to improve the quality of life of men with prostate cancer: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016 Dec;108:13–22.

• Michalski J, Mutic S, Eichling J, Ahmed SN. Radiation exposure to family and household members after prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2003 Jul;56(3):764–8.

• Mohamad H, McNeill G, Haseen F, N’Dow J, Craig LCA, Heys SD. The Effect of Dietary and Exercise Interventions on Body Weight in Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Nutr Cancer. 2015 Jan 2;67(1):43–60.

• Morris KA, Haboubi NY. Pelvic radiation therapy: Between delight and disaster. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015 Nov 27;7(11):279–88.

• Mottet N, Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Santis MD, Gillessen S, et al. EAU-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. European Association of Urology; 2022.

• Mourmouris P, Tzelves L, Deverakis T, Lazarou L, Tsirkas K, Fotsali A, et al. Prostate cancer therapies and fertility: What do we really know? Hell Urol. 2020;32(4):153.

• National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Biodegradable spacer insertion to reduce rectal toxicity during radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Interventional procedures guidance 590. 2017.

• National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management. 2021.

• Payne HA, Pinkawa M, Peedell C, Bhattacharyya SK, Woodward E, Miller LE. SpaceOAR hydrogel spacer injection prior to stereotactic body radiation therapy for men with localized prostate cancer: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Dec 10;100(49):e28111.

• Peinemann F, Grouven U, Bartel C, Sauerland S, Borchers H, Pinkawa M, et al. Permanent Interstitial Low-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy for Patients with Localised Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review of Randomised and Nonrandomised Controlled Clinical Trials. Eur Urol. 2011 Nov;60(5):881–93.

• Pettersson A, Johansson B, Persson C, Berglund A, Turesson I. Effects of a dietary intervention on acute gastrointestinal side effects and other aspects of health-related quality of life: A randomized controlled trial in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2012 Jun;103(3):333–40.

• Ralph S. Developing UK Guidance on How Long Men Should Abstain from Receiving Anal Sex before, During and after Interventions for Prostate Cancer. Clin Oncol. 2021 Dec;33(12):807–10.

• Richman EL, Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Paciorek A, Carroll PR, Chan JM. Physical Activity after Diagnosis and Risk of Prostate Cancer Progression: Data from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor. Cancer Res. 2011 May 24;71(11):3889–95.

• Royal College of Radiologists. Quality assurance practice guidelines for transperineal LDR permanent seed brachytherapy of prostate cancer. 2012.

• Saibishkumar EP, Borg J, Yeung I, Cummins-Holder C, Landon A, Crook J. Sequential Comparison of Seed Loss and Prostate Dosimetry of Stranded Seeds With Loose Seeds in 125I Permanent Implant for Low-Risk Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2009 Jan;73(1):61–8.

• Solanki AA, Liauw SL. Tobacco use and external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer: Influence on biochemical control and late toxicity: Prostate Radiation Toxicity in Smokers. Cancer. 2013 Aug 1;119(15):2807–14.

• Steinberger E, Kollmeier M, McBride S, Novak C, Pei X, Zelefsky MJ. Cigarette smoking during external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality and treatment-related toxicity. BJU Int. 2015 Oct;116(4):596–603.

• Stish BJ, Davis BJ, Mynderse LA, McLaren RH, Deufel CL, Choo R. Low dose rate prostate brachytherapy. Transl Androl Urol. 2018 Jun;7(3):341–56.

• Stone N. Complications Following Permanent Prostate Brachytherapy. Eur Urol. 2002 Apr;41(4):427–33.

• Storey DJ, McLaren DB, Atkinson MA, Butcher I, Liggatt S, O’Dea R, et al. Clinically relevant fatigue in recurrence-free prostate cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2012 Jan 1;23(1):65–72.

• Tillisch K. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2006 May 1;55(5):593–6.

• Tran S, Boissier R, Perrin J, Karsenty G, Lechevallier E. Review of the Different Treatments and Management for Prostate Cancer and Fertility. Urology. 2015 Nov;86(5):936–41.

• Wang LS, Murphy CT, Ruth K, Zaorsky NG, Smaldone MC, Sobczak ML, et al. Impact of obesity on outcomes after definitive dose-escalated intensity-modulated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2015 Sep 1;121(17):3010–7.

• Wedlake LJ, Shaw C, Whelan K, Andreyev HJN. Systematic review: the efficacy of nutritional interventions to counteract acute gastrointestinal toxicity during therapeutic pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jun;37(11):1046–56.

• White ID. Sexual Difficulties after Pelvic Radiotherapy: Improving Clinical Management. Clin Oncol. 2015 Nov;27(11):647–55.

• Wolff RF, Ryder S, Bossi A, Briganti A, Crook J, Henry A, et al. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials of radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Nov;51(16):2345–67.

• World Cancer Research Fund International. Continuous Update Project report: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Prostate Cancer [Internet]. 2014. Available from: www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Prostate-Cancer-2014-Report.pdf

• Zaorsky NG, Shaikh T, Murphy CT, Hallman MA, Hayes SB, Sobczak ML, et al. Comparison of outcomes and toxicities among radiation therapy treatment options for prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016 Jul;48:50–60.

- Peter Hoskin, Head of Brachytherapy and Gamma Knife Physics, St James's University Hospital, Leeds

- Ann Henry, Associate Professor in Clinical Oncology, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

- Our Specialist Nurses

- Our volunteers.