Trans women and prostate cancer

Do trans women have a prostate?

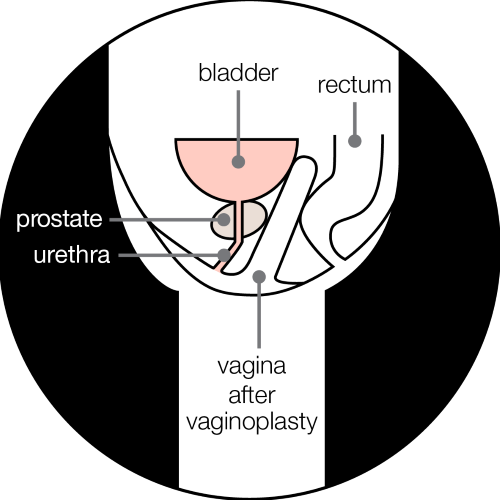

Yes. The prostate is a gland that sits under the bladder and surrounds the urethra, which is the tube that carries urine (wee) out of the body. It is not usually removed during gender affirming surgery, such as a vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty.

The following people have a prostate:

- cis men

- trans women

- non-binary people assigned male at birth

- some intersex people.

People assigned female at birth do not have a prostate so they can’t get prostate problems. Some intersex people assigned female at birth may have a prostate. Prostates are not put in or taken out as part of gender affirming surgery.

The information on this page is based on research about trans women. But some of it will be relevant to non-binary and intersex people who’ve had gender affirming surgery or taken feminising hormones.

In cis men, the prostate is usually the size of a walnut but gets bigger as you age. If you’re taking feminising hormones, such as oestrogen or drugs that block the effect of testosterone (testosterone blockers or anti-androgens), your prostate may grow less.

Having male bits and pieces is not easy – it is a nuisance – but I have always accepted I am a trans woman.

What does the prostate do in trans women?

The prostate’s main job is to help make semen – the fluid that carries sperm.

If you’ve had gender affirming surgery, you may still produce fluid on sexual arousal (seminal fluid) because you still have a prostate. But if you’ve had the testicles removed (orchidectomy), there won’t be any sperm in the fluid you produce.

How does having a prostate affect sex in trans women?

The prostate can provide lubrication during sex. Some trans women who have had a vaginoplasty still produce fluid from the prostate on sexual arousal. But not all trans women experience this.

The prostate gland is also sensitive. Stimulation of the prostate during vaginal penetration (including using fingers or sex toys) can be a source of sexual pleasure. The prostate can also be stimulated by anal penetration.

Will my prostate be removed during gender affirming surgery?

No. The prostate is not usually removed during gender affirming surgery (such as a vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty) because of the risk of side effects.

The prostate is close to the bladder and surrounded by nerves and blood vessels. Removing it can cause urinary problems and damage these nerves.

The prostate would only be removed during a vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty if the surgeon found a problem there, such as prostate cancer.

The prostate in a trans woman after a vaginoplasty

I didn’t know what prostate cancer was. I knew I had a prostate although I wasn’t told about it during transition. I have met many trans women who believe that the prostate is removed with genital reconstructive surgery, but it isn’t.

What prostate problems can I get?

Trans women, non-binary people assigned male at birth and some intersex people can get the same non-cancerous (benign) prostate problems as cis men, such as an enlarged prostate or prostatitis.

The symptoms of an enlarged prostate and prostatitis will be similar in trans women and cis men.

Can I get prostate cancer?

Yes. Your risk may be lower if you’ve taken feminising hormones, or had gender affirming surgery that included an orchidectomy. But there is still a risk, so it’s important to know the risk factors and be aware of the symptoms.

If you’re a non-binary person assigned male at birth and have not taken feminising hormones or had an orchidectomy, then your risk will be the same as for cis men.

I’ve always known that people born male have a prostate. It’s something that I have to live with. No health professional raised the risk of prostate problems with me, but I was aware that I was at risk.

If I’m taking hormones or have had gender affirming surgery, does that mean I won’t get prostate cancer?

No. You can still get prostate cancer if you’ve had surgery or are taking hormones - even if you’ve been taking them for a long time.

Your chance of developing prostate cancer may be lower if you’re taking testosterone blockers or anti-androgens, or if you’ve had an orchidectomy, because these lower your testosterone levels. Prostate cancer cells usually need testosterone to grow, so lowering your testosterone can reduce your risk.

Taking oestrogen can also lower your testosterone levels, and oestrogen is sometimes used to treat prostate cancer. But while oestrogen may lower your testosterone levels, some studies have shown that it may help prostate cancer cells to grow in people who have already developed prostate cancer. Oestrogen has also been linked to benign prostate problems, such as an enlarged prostate.

We still need more research about how oestrogen affects the prostate in trans women. If you are diagnosed with prostate cancer, your doctor might suggest that you change to a different type of oestrogen that is used to treat prostate cancer. But you won’t have to stop taking your feminising hormones if you don’t want to.

What is the risk of prostate cancer in trans women?

We don’t know the exact risk of prostate cancer in trans women. If you’re taking feminising hormones or have had an orchidectomy, you may have a lower risk of developing prostate cancer than cis men, but there is still a risk.

There is some evidence to suggest that if a trans woman has prostate cancer, it is likely to have started developing before they began taking feminising hormones. We need more research before we can say this for certain.

If you have not yet transitioned and are over 50 (or over 45 if you have any of the other risk factors), talk to your doctor about getting a prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test before you start to transition.

Early prostate cancer can be hard to diagnose in cis men because it often doesn’t cause any symptoms. Unfortunately, it can be harder to diagnose in trans women. There are a few reasons for this.

- You or your doctor might think that any urinary symptoms you experience are connected to your gender affirming surgery.

- If you are listed as female on your medical records, your doctor might not start a conversation with you about prostate health, or about having a PSA blood test if you have any of the risk factors.

- Some doctors may not be aware that the prostate is not removed as part of gender affirming surgery, such as a vaginoplasty or vulvoplasty. And some trans women may not have been told this when they had surgery.

- If you do have a test, your PSA levels (used to test if you might have a prostate problem) may be lower because you’re on feminising hormones. This may mean you are not referred for further tests unless your doctor is aware of this.

But if you know your individual risk, and how and when to get tested, then you have a better chance of catching prostate cancer early.

You can also get in touch with our Risk Information Service, who can help you understand your risk as a trans woman.

What are the risk factors for prostate cancer in trans women?

The risk factors for prostate cancer in trans women are:

- getting older – most cases of prostate cancer in trans women have been in those over 50

- being Black

- having a family history of prostate cancer.

People who have a family history of breast or ovarian cancer linked to a mutation (change) in the BRCA2 gene are also at an increased risk of prostate cancer.

If you don’t know whether you have a BRCA mutation, speak to your GP. They may be able to refer you for genetic testing.

How can I get tested for prostate cancer?

Testing for prostate cancer begins with a conversation with your GP. If you’re worried about your risk, speak to your GP. It will mean telling them you’re trans, but remember that conversations with health professionals are confidential, and they are required to treat you with respect.

Read our tips on having that conversation, and download our checklist for talking to your GP about prostate cancer.

You can also discuss your concerns with a doctor at an NHS gender dysphoria clinic, who may be able to refer you to a urologist.

Can I have a PSA blood test?

Yes – trans women, non-binary people assigned male at birth and some intersex people have the same right to a PSA blood test as cis men.

You have the right to a PSA blood test if you have thought carefully about the advantages and disadvantages of the test.

Should I get a PSA blood test before I medically transition?

If you medically transition later in life, your risk of prostate cancer may be higher. If you’re over 50 (or over 45 if you’re Black or have a family history), then ask your doctor about having the PSA blood test before you start taking feminising hormones or have an orchidectomy. This can help to establish your baseline PSA level.

Before you have the PSA blood test, discuss with your doctor what the test results might mean for your gender affirming surgery or hormone therapy. For example, if your PSA level is high, you might have to delay your transition while you have more tests.

If prostate cancer is found, your doctor will help you make choices about your treatment alongside your gender affirming care.

What are the symptoms of prostate cancer in trans women?

Most early prostate cancer doesn’t have any symptoms. That’s why it’s important to talk to your doctor about getting tested if you are worried or have any of the risk factors.

The symptoms of prostate cancer include:

- difficulty starting to urinate or emptying your bladder

- a weak flow when you urinate

- needing to urinate more often than usual, especially at night

- pain in one place in your bones.

Trans women who have prostate cancer may be less likely than cis men to get urinary symptoms. This is because taking feminising hormones may mean you have a smaller prostate. But having a smaller prostate doesn’t mean you can’t get prostate cancer or other prostate problems.

Urinary symptoms are sometimes caused by the prostate pressing on the urethra (the tube you wee through) as it grows. If you have a smaller prostate, it may take longer for the cancer cells to build up and start causing symptoms.

Urinary problems may also be a sign of a benign prostate problem, such as an enlarged prostate or prostatitis. Or they could be caused by an infection, another health problem such as diabetes, or any medicines you're taking.

Gender affirming surgery can also cause urinary symptoms and pain, which could be confused with symptoms of a prostate problem.

If you have any symptoms, speak to your GP so they can find out exactly what’s causing them and make sure you get the right treatment, if you need it.

Why isn’t there much information about trans women and prostate cancer?

We are still learning about prostate cancer in trans women. There are more studies now, but the number of trans women in these studies is often small, so it’s hard to know if the results will be similar for all trans women.

More evidence is needed before guidelines can be developed for healthcare professionals.

Getting support for prostate problems as a trans woman

Prostate Cancer UK’s services are free and open to everyone. Partners and family members can also use our services.

Our health information

On our website, we have other information for trans women on:

Our Specialist Nurses

Our Specialist Nurses can answer your questions and explain your diagnosis and treatment options.

All our Specialist Nurses can provide sensitive and appropriate support and information to trans women and non-binary people assigned male at birth.

Our online community

Our online community is a place to talk about whatever’s on your mind – your questions, your ups and your downs. Anyone can ask a question or share an experience.

The online community is open to all, and we have a dedicated section for trans women. Here, you can talk to others who may share or understand your experiences of prostate cancer and other prostate problems.

Who else can help?

Clinical services

The UK Cancer and Transition Service (UCATS) is an NHS clinic that supports trans and non-binary people affected by cancer. The service aims to help you manage your cancer and gender affirming care. There is also signposting to further support, and you can find out how to get involved in research.

If you have been diagnosed with prostate cancer, you can refer yourself to UCATS, or your doctor or nurse can refer you.

UCATS is part of TransPlus, which is a gender, sexual health and HIV service.

Support groups

At support groups, you can share your experiences of living with prostate cancer. You can also ask questions and share worries, knowing that people will understand what you’re going through.

These are support groups for gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer who also encourage trans women and non-binary and intersex people to attend:

OUTpatients provides support groups for any LGBTIQ+ person with and beyond cancer. They host regular peer support meetings and workshops and have a strong transgender representation.

Organisations

You may also find it helpful to contact organisations that support trans, intersex and non-binary people, such as:

References and reviewers

Updated: April 2025. To be reviewed: April 2028.

- Baraban E, Ding CKC, White M, Vohra P, Simko J, Boyle K, et al. Prostate Cancer in Male-to-Female Transgender Individuals: Histopathologic Findings and Association With Gender-affirming Hormonal Therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022 Dec;46(12):1650.

- Blasdel G, Borah L, Navarrete R, Howland R, Kuzon WM, Montgomery JS. “Prostatectomy after gender-affirming vaginoplasty for a transgender woman with prostate cancer”. Urol Case Rep. 2024 Sep 1;56:102819.

- Crowley F, Mihalopoulos M, Gaglani S, Tewari AK, Tsao CK, Djordjevic M, et al. Prostate cancer in transgender women: considerations for screening, diagnosis and management. Br J Cancer. 2023 Jan;128(2):177–89.

- de Nie I, de Blok CJM, van der Sluis TM, Barbé E, Pigot GLS, Wiepjes CM, et al. Prostate Cancer Incidence under Androgen Deprivation: Nationwide Cohort Study in Trans Women Receiving Hormone Treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Sep 1;105(9):e3293–9.

- Deebel NA, Morin JP, Autorino R, Vince R, Grob B, Hampton LJ. Prostate Cancer in Transgender Women: Incidence, Etiopathogenesis, and Management Challenges. Urology. 2017 Dec 1;110:166–71.

- Electonic Medicines Compendium. Diethylstilbestrol 1mg film-coated tablet - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc) [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/13401/smpc#about-medicine

- Gooren L, Morgentaler A. Prostate cancer incidence in orchidectomised male-to-female transsexual persons treated with oestrogens. Andrologia. 2014 Dec;46(10):1156–60.

- Hanley K, Wittenberg H, Gurjala D, Safir MH, Chen EH. Caring for Transgender Patients: Complications of Gender-Affirming Genital Surgeries. Ann Emerg Med. 2021 Sep 1;78(3):409–15.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, Hannema SE, Meyer WJ, Murad MH, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov 1;102(11):3869–903.

- JIN B, TURNER L, WALTERS WAW, HANDELSMAN DJ. Androgen or Estrogen Effects on Human Prostate. M . 1996;6.

- Kalavacherla S, Riviere P, Kalavacherla S, Anger JT, Murphy JD, Rose BS. Prostate Cancer Screening Uptake in Transgender Women. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Feb 14;7(2):e2356088.

- Lafront C, Germain L, Campolina-Silva GH, Weidmann C, Berthiaume L, Hovington H, et al. The estrogen signaling pathway reprograms prostate cancer cell metabolism and supports proliferation and disease progression. J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2024 Jun 3 [cited 2025 Mar 12];134(11). Available from: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/170809

- Loria M, Gilbert D, Tabernacki T, Maravillas MA, McNamara M, Gupta S, et al. Incidence of prostate cancer in transgender women in the US: a large database analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024 Feb 7;1–3.

- Ma SJ, Oladeru OT, Wang K, Attwood K, Singh AK, Haas-Kogan DA, et al. Prostate Cancer Screening Patterns Among Sexual and Gender Minority Individuals. Eur Urol. 2021 May 1;79(5):588–92.

- Manfredi C, Ditonno F, Franco A, Bologna E, Licari LC, Arcaniolo D, et al. Prostate Cancer in Transgender Women: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, and Management Challenges. Curr Oncol Rep [Internet]. 2023 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Nov 7]; Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11912-023-01470-w

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng131

- Nicholson TM, Ricke WA. Androgens and estrogens in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Past, present and future. Differentiation. 2011 Nov 1;82(4):184–99.

- Nik-Ahd F, De Hoedt AM, Butler C, Anger JT, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prostate-Specific Antigen Values in Transgender Women Receiving Estrogen. JAMA. 2024 Jul 23;332(4):335–7.

- Nik-Ahd F, Jarjour A, Figueiredo J, Anger JT, Garcia M, Carroll PR, et al. Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening in Transgender Patients. Eur Urol. 2023 Jan 1;83(1):48–54.

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, Vadaparampil ST, Nguyen GT, Green BL, et al. Cancer and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender/Transsexual, and Queer/Questioning Populations (LGBTQ). CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Sep;65(5):384–400.

- Rees J, Bultitude M, Challacombe B. The management of lower urinary tract symptoms in men. BMJ. 2014 Jun 24;348(1):g3861–g3861.

- Reis LO, Zani EL, García-Perdomo HA. Estrogen therapy in patients with prostate cancer: a contemporary systematic review. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018 Jun 1;50(6):993–1003.

- Weyers S, De Sutter P, Hoebeke S, Monstrey G, ’T Sjoen G, Verstraelen H, et al. Gynaecological aspects of the treatment and follow-up of transsexual men and women. Facts Views Vis ObGyn. 2010;2(1):35–

- Xu G, Dai G, Huang Z, Guan Q, Du C, Xu X. The Etiology and Pathogenesis of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: The Roles of Sex Hormones and Anatomy. Res Rep Urol. 2024 Sep 23;16:205–14.

- Alison Berner, Honorary Consultant and Academic Clinical Lecturer in Medical Oncology, Specialty Doctor in Adult Gender Identity Medicine, Queen Mary University of London/Barts Health NHS Trust/Chelsea & Westminster Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

- Ashley d’Aquino, Lecturer Practitioner, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust

- Katherine Read, Radiotherapy Review Radiographer, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust

- Laura Hinchliffe, Clinical Director, Cardiff Local Gender Service

- Oliver Hulson, Consultant Radiologist, Leeds Cancer Centre

- Shaina Tennant, Medical Writer, Wallace Health: wallacehealth.co.uk/

- Stewart O'Callaghan, Founder & Chief Executive Officer, OUTpatients: https://outpatients.org.uk/

- Our Specialist Nurses

- Our Volunteers.