Prostate biopsy

Improving our information

This webpage is due to be reviewed shortly. To make sure it as accurate and accessible we want to hear your thoughts by completing a short survey on what you have read today. It should take no longer than three minutes.

What is a prostate biopsy?

A prostate biopsy involves using a thin needle to take small samples of tissue from the prostate. The tissue is then looked at under a microscope to check for cancer. If cancer is found, the biopsy results will show how aggressive it is – in other words, how likely it is to spread outside the prostate.

There are two main types of prostate biopsy:

Talk to your doctor or nurse about whether you will have a TRUS biopsy or a transperineal biopsy.

In many hospitals you may have a special type of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, called a multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) scan, before having a biopsy. In other hospitals you may have a biopsy first.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of having a biopsy?

Your doctor should talk to you about the advantages and disadvantages of having a biopsy. If you have any concerns, discuss them with your doctor or specialist nurse before you decide whether to have a biopsy.

Advantages

- It’s the only way to find out for certain if you have cancer inside your prostate.

- It can help find out how aggressive any cancer might be – in other words, how likely it is to spread.

- It can pick up a faster growing cancer at an early stage, when treatment may prevent the cancer from spreading to other parts of the body.

- If you have prostate cancer, it can help your doctor or nurse decide which treatment options may be suitable for you.

- If you have prostate cancer, you’ll usually need to have had a biopsy if you want to join a clinical trial in the future. This is because the researchers may need to know what your cancer was like when it was first diagnosed.

Disadvantages

- The biopsy can only show whether there was cancer in the samples taken, so it’s possible that cancer might be missed.

- It can pick up a slow growing or non-aggressive cancer that might not cause any symptoms or problems in your lifetime. You would then have to decide whether to have treatment or to have your cancer monitored. Having your cancer monitored instead of having treatment might make you worry. But having treatment can cause side effects that can be hard to live with.

- A biopsy has side effects and risks, including the risk of getting a serious infection.

- If you take medicines to thin your blood, you may need to stop taking them for a while, as the biopsy can cause some bleeding for a couple of weeks.

What does a prostate biopsy involve?

If you decide to have a biopsy, you’ll either be given an appointment to come back to the hospital at a later date or offered the biopsy straight away.

Before the biopsy you should tell your doctor or nurse if you’re taking any medicines, particularly antibiotics or medicines that thin the blood such as warfarin or aspirin.

You may be given some antibiotics to take before your biopsy, either as tablets or an injection, to help prevent infection. You might also be given some antibiotic tablets to take at home after your biopsy. It’s important to take them all so that they work properly.

A doctor or nurse will do the biopsy. There are two main types of biopsy:

- a trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biopsy, where the needle goes through the wall of the back passage

- a transperineal biopsy, where the needle goes through the skin between the testicles and the back passage (the perineum).

The type of biopsy you will have depends on your hospital.

What is a TRUS biopsy?

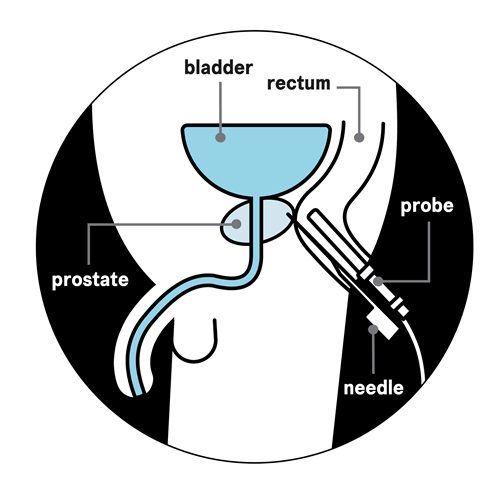

The doctor or nurse uses a thin needle to take small samples of tissue from the prostate through the wall of the back passage (rectum).

You’ll lie on your side on an examination table, with your knees brought up towards your chest. The doctor or nurse will put an ultrasound probe into your back passage (rectum), using a gel to make it more comfortable. The ultrasound probe scans the prostate and an image appears on a screen. The doctor or nurse uses this image to guide where they take the cells from. If you’ve had an MRI scan, the doctor or nurse may use the images to decide which areas of the prostate to take biopsy samples from.

You will have an injection of local anaesthetic to numb the area around your prostate and reduce any discomfort. The doctor or nurse then puts a needle next to the probe in your back passage and inserts it through the wall of the back passage into the prostate. They usually take 10 to 12 small pieces of tissue from different areas of the prostate. But, if the doctor is using the images from your MRI scan to guide the needle, they may take fewer samples.

The biopsy takes 5 to 10 minutes. After your biopsy, your doctor may ask you to wait until you've urinated before you go home. This is because the biopsy can cause the prostate to swell, so they'll want to make sure you can urinate properly before you leave. You should ask your doctor or nurse if you need to get someone to take you home or if you can drive yourself home.

What is a transperineal biopsy?

This is where the doctor inserts the biopsy needle into the prostate through the skin between the testicles and the back passage (perineum).

A transperineal biopsy can be done under either general anaesthetic or local anaesthetic. If you have a biopsy under general anaesthetic, you will be asleep and won’t feel anything. A general anaesthetic can cause side effects – your doctor or nurse should explain these before you have your biopsy.

If you have a biopsy using a local anaesthetic, you are awake during the procedure and the anaesthetic numbs the prostate and the area around it.

The doctor will put an ultrasound probe into your back passage, using a gel to make this easier. An image of the prostate will appear on a screen, which will help the doctor to guide the biopsy needle.

There are two main types of transperineal biopsy you may have:

A targeted transperineal biopsy. This is where the doctor may just take a few samples from the area of the prostate that looked unusual on the scan images from your MRI.

A template transperineal biopsy. This is where the doctor places a grid (template) over the area of skin between the testicles and back package. They then insert the needle though holes in the grid, into the prostate. They might take up to 25 or more samples from different areas of the prostate. A template biopsy is sometimes used if a TRUS biopsy hasn’t found any cancer, but the doctor still thinks there might be cancer.

A transperineal biopsy usually takes about 20 to 40 minutes. You will need to wait a few hours to recover from the anaesthetic before going home. You should ask your doctor or nurse if you need to get someone to take you home or if you can drive yourself home. Your doctor may ask you to wait until you’ve urinated. This is because the biopsy can cause the prostate to swell, so they’ll want to make sure you can urinate properly before you leave.

What are the side effects of a biopsy?

Having a biopsy can cause side effects. These will affect each man differently, and you may not get all of the possible side effects.

Some men feel pain or discomfort in their back passage (rectum) for a few days after a TRUS biopsy. Others feel a dull ache along the underside of their penis or lower abdomen (stomach area). If you have a transperineal biopsy, you may get some bruising and discomfort in the area where the needle went in for a few days afterwards.

If you receive anal sex, wait about two weeks, or until any pain or discomfort from your biopsy has settled, before having sex again. Ask your doctor or nurse at the hospital for further advice.

Some men find the biopsy painful, but others have only slight discomfort. Your nurse or doctor may suggest taking mild pain-relieving drugs, such as paracetamol, to help with any pain.

If you have any pain or discomfort that doesn’t go away, talk to your nurse or doctor.

It’s normal to see a small amount of blood in your urine or bowel movements for about two weeks.

You may also notice blood in your semen for a couple of months – it might look red or dark brown. This is normal and should get better by itself. If it takes longer to clear up, or gets worse, you should see a doctor straight away.

A small number of men who have a TRUS biopsy may have more serious bleeding in their urine or from their back passage (rectum). This can also happen if you have a transperineal biopsy, but it isn’t very common. If you have severe bleeding or are passing lots of blood clots, this is not normal. Contact your doctor or nurse at the hospital straight away, or go to the accident and emergency (A&E) department at the hospital.

Some men get an infection after their biopsy. This is more likely after a TRUS biopsy than after a transperineal biopsy. It's very important to take any antibiotics you’re given, as prescribed, to help prevent this. But you might still get an infection even if you take antibiotics.

Symptoms of a urine infection may include:

- pain or a burning feeling when you urinate

- dark or cloudy urine with a strong smell

- needing to urinate more urgently than usual

- needing to urinate more often than usual during the day or night

- a high or very low temperature

- pain in your lower abdomen (stomach area) or back.

If you have any of these symptoms, contact your doctor or nurse at the hospital straight away. If you can’t get in touch with them, call your GP.

Less than 1 in 100 men (one per cent) who have a TRUS biopsy get a more serious infection that requires going to hospital. If the infection spreads into your blood, it can be very serious. This is called sepsis. Symptoms of sepsis may include:

- a high temperature (fever)

- chills and shivering

- blue, pale or blotchy skin, lips or tongue

- a fast heartbeat

- fast breathing or difficulty breathing

- confusion or changes in behaviour.

If you have symptoms of sepsis, go to your nearest hospital A&E department straight away.

A small number of men find they suddenly and painfully can’t urinate after a biopsy – this is called acute urine retention. This happens because the biopsy can cause the prostate to swell, making it difficult to urinate. Acute urine retention may be more likely if you have a template biopsy. This is because more samples are taken, so there may be more swelling.

Your doctor will make sure you can urinate before you go home after your biopsy. If you can’t urinate, you might need to have a catheter for a few days at home – this is a thin tube that’s passed into your bladder to drain urine out of the body.

If you develop acute urine retention at home, contact your doctor or nurse at the hospital straight away, or go to your nearest A&E department. You might need a catheter for a few days.

You can masturbate and have sex after a biopsy. If you have blood in your semen, you might want to use a condom until the bleeding stops.

A small number of men have problems getting or keeping an erection (erectile dysfunction) after having a biopsy. This may happen if the nerves that control erections are damaged during the biopsy. It isn’t very common and it should get better over time, usually within two months. Speak to your doctor or nurse if you’re worried about this.

Getting my biopsy results

It can take up to two weeks to get the results of the biopsy, but it can take longer in some hospitals.

Your biopsy samples will be looked at under a microscope to check for any cancer cells. Your doctor will be sent a report, called a pathology report, with the results. The results will show whether any cancer was found. They may also show how many biopsy samples contained cancer and how much cancer was present in each sample.

You might be sent a copy of the pathology report. If you have trouble understanding any of the information, ask your doctor to explain it or speak to our Specialist Nurses.

If cancer is found

If cancer is found, this is likely to be a big shock, and you might not remember everything your doctor or nurse tells you. It can help to take a family member, partner or friend with you for support when you get the results. You could also ask them to make some notes during the appointment.

It could help to ask your doctor if you can record the appointment. You have a right to record your appointment if you would like to because it’s your personal data. But let your doctor or nurse know if and why you are recording them as not everyone is comfortable being recorded.

How likely is my prostate cancer to spread?

Your biopsy results will show how aggressive the cancer is – in other words, how likely it is to spread outside the prostate. You might hear this called your Gleason grade, Gleason score or grade group.

Read more about what your biopsy results mean, including how likely your cancer is to spread.

What type of prostate cancer do I have?

Your doctor will look at your biopsy results to see what type of prostate cancer you have.

For most people who are diagnosed, the type of prostate cancer is called adenocarcinoma or acinar adenocarcinoma – you might see this written on your biopsy report. There are other types of prostate cancer that are very rare. Read more about rare prostate cancers.

What happens next?

Your doctor or nurse will talk you through what your results mean. You might need scans to find out whether the cancer has spread outside the prostate and where it has spread to.

Your doctor will look at all of your test results with a team of health professionals. You might hear this called your multi-disciplinary team (MDT). Based on your results, you and your doctor will talk about the next best step for you. Read our information for those who've just been diagnosed.

If no cancer is found

If no cancer is found this is likely to be reassuring. However, this means ‘no cancer has been found’ rather than ‘there is no cancer’. Sometimes, there could be some cancer that was missed by the biopsy needle.

What happens next?

Your doctor will look at your other test results and your risk of prostate cancer so that you can discuss what to do next.

If your doctor thinks you may have prostate cancer that hasn’t been found, they might suggest having another biopsy or an MRI scan.

If your doctor thinks you probably don’t have prostate cancer, they may offer to monitor your prostate with regular PSA tests to see if there are any changes in the future.

What else might the biopsy results show?

Sometimes a biopsy may find other changes to your prostate cells, called prostate intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) or atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP). Read more about PIN and ASAP.

References and reviewers

Updated June 2025|To be reviewed June 2026

- Berney DM. The case for modifying the Gleason grading system. BJU Int. 2007;100(4):725–6.

- Borghesi M, Ahmed H, Nam R, Schaeffer E, Schiavina R, Taneja S, et al. Complications After Systematic, Random, and Image-guided Prostate Biopsy. Eur Urol. 2017 Mar 1;71(3):353–65.

- Buskirk SJ, Pinkstaff DM, Petrou SP, Wehle MJ, Broderick GA, Young PR, et al. Acute urinary retention after transperineal template-guided prostate biopsy. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2004 Aug;59(5):1360–6.

- Cornford P, Tilki D, van der Bergh RCN, Eberli D, De Meerleer G, De Santis M, et al. EAU - EANM - ESTRO - ESUR - ISUP - SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. European Association of Urology; 2025.

- Dyson M. Patients recording consultations [Internet]. The British Medical Association. [cited 2022 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/ethics/confidentiality-and-health-records/patients-recording-consultations

- Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Humphrey PA, et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(2):244–52.

- Kasivisvanathan V, Rannikko AS, Borghi M, Panebianco V, Mynderse LA, Vaarala MH, et al. MRI-Targeted or Standard Biopsy for Prostate-Cancer Diagnosis. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2018 Mar 18 [cited 2018 May 4]; Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1801993

- Loeb S, Vellekoop A, Ahmed HU, Catto J, Emberton M, Nam R, et al. Systematic review of complications of prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2013 Dec;64(6):876–92.

- Moch H, Humphrey PA, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE, editors. WHO Classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs [Internet]. 4th ed. Vol. 8. World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/bookorders/anglais/detart1.jsp?codlan=1&codcol=70&codcch=4008

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng131

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Suspected sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. 2024; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transperineal template biopsy and mapping of the prostate. 2010.

- National Prostate Cancer Audit. NPCA Annual Report 2021 [Internet]. National Prostate Cancer Audit. [cited 2022 Feb 4]. Available from: https://www.npca.org.uk/reports/npca-

- NHS. Prostate cancer - Diagnosis [Internet]. nhs.uk. 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/prostate-cancer/diagnosis/

- NHS. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) [Internet]. nhs.uk. 2022 [cited 2025 May 28]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-tract-infections-utis/

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Advising men without symptoms of prostate disease who ask about the PSA test [Internet]. GOV.UK. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prostate-specific-antigen-testing-explanation-and-implementation/advising-well-men-about-the-psa-test-for-prostate-cancer-information-for-gps

- Pinkstaff DM, Igel TC, Petrou SP, Broderick GA, Wehle MJ, Young PR. Systematic transperineal ultrasound-guided template biopsy of the prostate: Three-year experience. Urology. 2005 Apr;65(4):735–9.

- Rosario DJ, Lane JA, Metcalfe C, Donovan JL, Doble A, Goodwin L, et al. Short term outcomes of prostate biopsy in men tested for cancer by prostate specific antigen: prospective evaluation within ProtecT study. BMJ. 2012;344:d7894.

- Xue J, Qin Z, Cai H, Zhang C, Li X, Xu W, et al. Comparison between transrectal and transperineal prostate biopsy for detection of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(14):23322.

- Our Health information team

- Our Specialist Nurses