Prostate cancer diagnosis in trans women

If you are a trans woman or non-binary person assigned male at birth you can get prostate cancer. So if you are worried about your risk or any symptoms, it’s important to talk to your doctor. The tests you have will depend on your history and any treatment you’re currently taking.

Read our information on tests for prostate cancer. A lot of the information will still be relevant to you if you have taken feminising hormones or testosterone blockers or had genital reconstructive surgery, but you can read below about some of the ways tests will vary.

Just like cis men, it’s likely that the risk of prostate cancer increases from the age of 50 in trans women and non-binary people assigned male at birth. Read more about your risk of prostate cancer. There is thought to be a lower risk of prostate cancer in trans women than in cis men.

If you have any symptoms or are concerned about your risk of prostate cancer, you should speak to a GP.

You can find a GP if you don't have one here:

- nhs.uk in England

- nhsinform.scot in Scotland

- nhsdirect.wales.nhs.uk in Wales

- hscni.net in Northern Ireland

Tests for trans women at the GP surgery

Your GP might give you a urine test, a PSA test (blood test) and a prostate examination. They may then refer you to a urologist for more information and further tests if necessary. You can also discuss your concerns with a doctor at a gender identity clinic, who may refer you to a urologist.

PSA test in trans women

If you’re a trans women over the age of 50, you can discuss your risk of prostate cancer with your doctor, even if you don’t have symptoms.

Most experts think you should have a PSA test (blood test) before starting feminising hormones or testosterone blockers if you’re aged 50 or over, or over the age of 45 if you have a family history of prostate cancer or if you are black.

It’s best to discuss your situation with your doctor as there are advantages and disadvantages of having tests.

Because feminising hormones, testosterone blockers and testicle removal can lower PSA levels, some experts believe that a PSA level above 1 ng/ml should be investigated further.

Prostate examination

Sometimes, a doctor will think it’s necessary to feel your prostate using a finger. If you’re a trans woman or a non-binary person assigned male at birth who has not had any genital reconstructive surgery, or you have had a labiaplasty (rather than a vaginoplasty), you’ll have a digital rectal examination. This is where your doctor feels your prostate through the wall of your back passage (rectum).

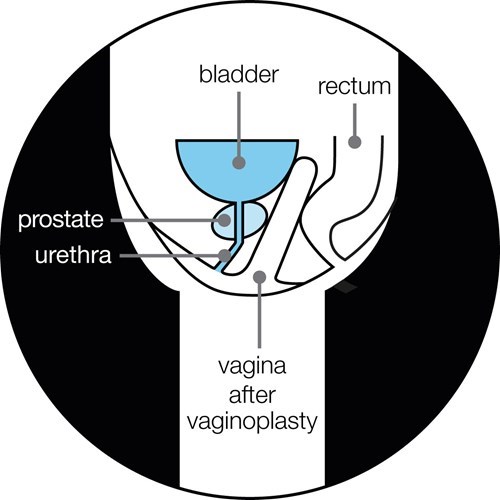

If you’ve had genital reconstructive surgery that includes vaginoplasty (the formation of a vagina) then your prostate may be examined through the vagina (see diagram below).

Tests for trans women at the hospital

After the tests at your GP surgery, you may have further tests at a hospital. These can include an MRI scan and/or a biopsy.

Often you may be seen in a clinic attended by cis men. On arrival, you should take your referral letter to the receptionist who should treat you with courtesy and refer to you by name. You do not have to explain your reasons for attending the clinic to the reception staff nor to any other patients.

Some trans women may find it uncomfortable waiting to see a urologist in a room full of men. You might find it helps to take someone with you, or a book or magazine to read while you wait.

Most clinics will try to be accommodating, putting you on the end or beginning of the list rather than in the middle of it. Read more about talking to health professionals.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan

An MRI scan is done in the same way as in a cis man. Read about what an MRI scan involves. You might have to wait a few weeks for a scan if you’ve recently had genital reconstructive surgery.

Biopsy

A biopsy will either be a transperineal biopsy or a trans-rectal ultrasound (TRUS) guided biospy.

If you’ve had genital reconstructive surgery that includes vaginoplasty then you may have a biopsy via the vagina or other routes. The urologist doing the biopsy will look at your scans before discussing the best approach with you.

Speaking to a health professional about prostate cancer

If you’re a trans woman or non-binary person assigned male at birth, you might feel uncomfortable going to your doctor to talk about possible prostate problems. This might be because you don’t wish to be ‘outed’ or you may feel worried about being treated as male. You may also feel anxious about having tests for prostate cancer and fear they will be invasive.

Remember that your conversations with health professionals are confidential and they must treat you with respect. This includes using the correct names and pronouns on your records, at reception and during treatments and consultations. Read more about your right to be treated equally to everyone else. If a doctor tells you they do not know anything about prostate care for trans people, they have a duty of care to find out.

It’s important that you feel comfortable with the GP you’re seeing. If you find that you’re not, or if they don’t use your chosen pronoun and name, you have the right to make a complaint and ask to see someone else. You can ask to see another GP in the same practice or register with a new practice. You could also ask to be referred to a gender identity clinic (if you’re not already under the care of one) or a urologist.

What to say

Start by explaining that you have a prostate – and mention any symptoms or family history of prostate cancer. Tell the doctor about any history of hormonal treatment and testicle removal. You don’t have to reveal your trans history to a health professional unless you want to, but it will help them give you the best care.

Healthcare professionals should discuss with you how and what medical information you wish to be recorded and shared. For example, all of your history may not be relevant. But some medical information, such as how long you have been taking feminising hormones or testosterone blockers and any surgical procedures, is relevant to prostate health.

Many health professionals won’t have seen trans people with prostate problems (or even trans people at all) so you might need to take a role in educating them. The checklist below may help you remember what to say. If your doctor is unsure about prostate problems in trans women, they can contact a gender identity clinic for expert guidance.

If you feel embarrassed about starting a conversation about prostate problems, then try taking this information with you. Or download this checklist for talking to your GP about prostate cancer as a trans woman.

References and reviewers

Updated: October 2020. To be reviewed: October 2023.

- Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2016 July;83:531-541. Best practices in LGBT care: A guide for primary care physicians. Accessed May 30, 2017. http://www.mdedge.com/ccjm/article/109822/adolescent-medicine/best-practices-lgbt-care-guide-primary-care-physicians

- Deebel NA, Morin JP, Autorino R, Vince R, Grob B, Hampton LJ. Prostate Cancer in Transgender Women: Incidence, Etiopathogenesis, and Management Challenges. Urology. Published online September 2017. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.032

- Epstein JI. PSA and PAP as immunohistochemical markers in prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 1993;20(4):757-770.

- Jonathan Goddard. DETECTION OF PROSTATE CANCER FOLLOWING GENDER REASSIGNMENT: LETTERS. BJU Int. 2007;101(2):259-259. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07394_4.x

- Gooren L, Morgentaler A. Prostate cancer incidence in orchidectomised male-to-female transsexual persons treated with oestrogens. Andrologia. 2014;46(10):1156-1160. doi:10.1111/and.12208

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903. doi:10.1210/jc.2017-01658

- Mcnamara MC, Ng H. Best practices in LGBT care: A guide for primary care physicians. Cleve Clin J Med. 2016;83(7):531-541. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15148

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender/Transsexual, and Queer/Questioning Populations (LGBTQ). CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):384-400. doi:10.3322/caac.21288

- Turo R, Jallad S, Cross WR, Prescott S. Metastatic prostate cancer in transsexual diagnosed after three decades of estrogen therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(7-8). doi:10.5489/cuaj.175

- Unger CA. Care of the transgender patient: the role of the gynecologist. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):16-26. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.035

- Weyers S, Decaestecker K, Verstraelen H, et al. Clinical and Transvaginal Sonographic Evaluation of the Prostate in Transsexual Women. Urology. 2009;74(1):191-196. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.016

- James Bellringer, Consultant Gender and Urological Surgeon, Parkside Hospital, London

- Alison May Berner, Specialist Registrar and Clinical Research Fellow in Medical Oncology and Adult Gender Identity, Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, London

- Frank Chinegwundoh, Consultant Urological Surgeon, Barts Health NHS Trust

- Jonny Coxon, Speciality Doctor, Gender Identity Clinic, London

- Oliver Hulson, Consultant Radiologist, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

- Chidi Molokwu, Consultant Urologist & Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer, Urology & Cancer Therapeutics, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust & University of Bradford

- Joe O'Sullivan, Consultant Prostate Oncologist, Queen's University Belfast

- Tina Rashid, Consultant in Functional Urology and Genital Reconstruction, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London

- Vijay K. Sangar, Consultant Urological Surgeon, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust & Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

- Our Specialist Nurses

- Our Volunteers.