Managing symptoms in advanced prostate cancer

Men who have prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body (advanced prostate cancer) might get some of the symptoms we describe on this page. The symptoms you have will depend on where the cancer has spread to and how quickly it is growing. You might only get a few symptoms and they might not affect you every day. But the cancer might spread further over time, causing symptoms that affect you more.

There are treatments available to help manage symptoms and other things that can help.

If you haven’t been diagnosed with prostate cancer, but want to find out more about what to look out for, you can read our information on prostate cancer signs and symptoms.

Fatigue (extreme tiredness)

Fatigue is a feeling of extreme tiredness that doesn’t go away, even after you rest. It is very common in men with advanced prostate cancer.

Many men are surprised by how tired they feel and by the impact this has on their lives. Fatigue can make it difficult to do some things, including:

- everyday tasks, such as getting dressed, having a shower or preparing food

- social activities, such as seeing friends and family

- sleeping (insomnia)

- concentrating

- remembering things

- understanding new information and making decisions.

Fatigue can also affect your mood. It might make you feel sad, depressed or anxious. You may feel guilty or frustrated that you can’t do the things you normally do. It can also affect your relationships.

Fatigue can be caused by lots of things, such as:

- prostate cancer itself

- treatments for prostate cancer

- stress, anxiety or depression

- symptoms of advanced prostate cancer, such as pain or anaemia

- other health problems

- not sleeping well

- lack of physical activity.

What can help?

There are lots of things you can do to improve or manage your fatigue. Small changes to your life can make a big difference.

Things you might want to try include:

- being as physically active as you can – this can help improve your energy levels, sleep, mood and general health

- getting help with emotional problems

- planning activities for when you usually have more energy – maybe first thing in the morning, or in the afternoon after a rest

- making time to rest and relax

- dealing with any problems sleeping – try to relax before bed and avoid drinks with caffeine, such as tea and coffee, as these can keep you awake

- eating a well-balanced diet

- trying complementary therapies alongside your usual treatment

- asking for help if you need it, for example with shopping or jobs around the house.

I found exercise was a good way to manage my fatigue. It motivated me and helped keep my spirits up.

Pain

Pain is a common problem for men with advanced prostate cancer, although some men have no pain at all. The cancer can cause pain in the areas it has spread to. If you do have pain, it can usually be relieved or reduced, with the right treatment and management.

Pain is more common in men whose cancer has spread to their bones. The cancer can damage or weaken the bone, which may cause pain. But not all men with cancer in their bones will get bone pain. A bone scan can show whether areas of your bones have been weakened. The areas that show up on a scan are sometimes called ‘hot spots’.

Bone pain is a very specific feeling. Some men describe it as feeling similar to a toothache but in the bones, or like a dull aching or stabbing. It can get worse when you move and can make the area tender to touch. Each man’s experience of bone pain will be different. The pain may be constant or it might come and go. How bad it is can also vary, and may depend on where the affected bone is.

You might get other types of pain. For example, if the cancer presses on a nerve, this can also cause pain. This might be shooting, stabbing, burning, tingling or numbness.

Pain can also be a symptom of a more serious condition called metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC).

What can help?

By trying different treatments, or combinations of treatments, pain from cancer can usually be managed well. You shouldn’t have to accept pain as a normal part of having cancer. If you have pain, speak to your doctor or nurse. The earlier pain is treated, the easier it will be to control.

Different types of pain are treated in different ways. Treatments to control pain include:

- treatment for the cancer itself, such as hormone therapy, steroids, chemotherapy or a type of internal radiotherapy called radium-223 (Xofigo®)

- treatment for the pain, such as pain-relieving drugs, radiotherapy, bisphosphonates, surgery to support damaged bone, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), or a nerve block.

Other things that might help you manage your pain include:

- complementary therapies

- getting emotional support

- treatments for other causes of pain, such as antibiotics to treat infection

- keeping a pain diary to help you describe the pain to your doctor or nurse – download one from our website.

- eating a healthy diet and doing regular gentle exercise.

To find the best way to deal with your pain, you might have a pain assessment and be referred to a palliative care specialist. Palliative care specialists provide treatment to manage pain and other symptoms of advanced cancer.

I kept a pain diary and took it to my appointments. This made it easier to describe my pain.

Urinary problems

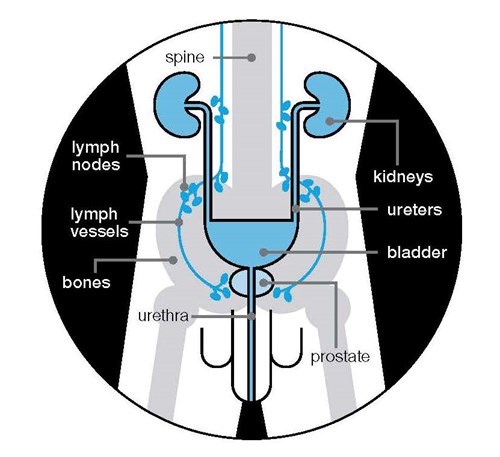

You might get urinary problems if the cancer is pressing on your urethra or has spread to areas around the prostate, such as the urethra and bladder.

Problems might include:

- problems emptying your bladder

- leaking urine (incontinence)

- blood in your urine

- kidney problems.

Some treatments for prostate cancer, such as surgery or radiotherapy, can also cause urinary problems. Read more about managing these problems.

Urinary problems can also be caused by an infection or an enlarged prostate. If you have urinary problems, speak to your doctor or nurse. There are lots of things that can help.

Problems emptying your bladder

If the cancer is pressing on your urethra or the opening of your bladder, you may find it difficult to empty your bladder fully. This can sometimes cause urine retention, where urine is left in your bladder when you urinate. There are several things that can help, including the following.

- Drugs called alpha-blockers. These relax the muscles around the opening of the bladder, making it easier to urinate.

- A catheter to drain urine from the bladder. This is a thin, flexible tube that is passed up your penis into your bladder, or through a small cut in your abdomen (stomach area).

- An operation called a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) to remove the parts of the prostate that are pressing on the urethra.

Acute urine retention

This is when you suddenly and painfully can’t urinate at all – it needs treating straight away. Acute retention isn’t very common in men with advanced prostate cancer. But if it happens, call your doctor or nurse, or go to your nearest accident and emergency (A&E) department. They may need to drain your bladder using a catheter.

Leaking urine

Cancer can grow into the bladder and the muscles that control urination, making the muscles weaker. This could mean you leak urine or need to urinate urgently. Ways to manage leaking urine include:

- absorbent pads and pants

- pelvic floor muscle exercises

- medicines called anti-cholinergics

- a catheter

- surgery.

Read more about things to help with leaking urine.

Your treatment options will depend on how much urine you’re leaking and what treatments are suitable for you. Your GP may refer you to an NHS continence service, run by specialist nurses and physiotherapists. The Continence Product Advisor website has information about incontinence products.

If you find you need to rush to the toilet a lot and sometimes leak before you get there, find out where there are public toilets before you go out. The Great British Public Toilet Map website has information about where there are public toilets. Get our Urgent toilet card to show to staff in shops or restaurants – this should make it easier to ask to use their toilet.

Rarely, problems emptying your bladder or leaking urine may be caused by a condition called metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC).

Blood in your urine

Some men notice blood in their urine (haematuria). This may be caused by bleeding from the prostate. It can be alarming, but can usually be managed.

Your doctor might ask you to stop taking medicines that thin your blood, such as aspirin or warfarin. Speak to your doctor or nurse before you stop taking any drugs. You might also be able to have radiotherapy to shrink the cancer and help to stop the bleeding.

Kidney problems

The kidneys remove waste products from your blood and produce urine. Prostate cancer may block the tubes that carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder (ureters). This can affect how well your kidneys work. Prostate cancer and some treatments can also make it difficult to empty your bladder (which can lead to urine retention). This can stop your bladder and kidneys from draining properly, which can cause kidney problems.

Severe kidney problems can lead to high levels of waste products in your blood, which can be harmful. Symptoms include:

- tiredness and lack of energy

- feeling sick

- swollen ankles and feet

- poor appetite.

If you have any of these symptoms tell your doctor or nurse. A blood test can check how well your kidneys are working.

Treatments that can help to drain urine from the kidneys include:

- a tube put into the kidney to drain urine into a bag outside your body (nephrostomy)

- a tube (called a stent) put inside one or both ureters to allow urine to flow from the kidney to the bladder

- radiotherapy to shrink the cancer and reduce the blockage.

If you have kidney problems caused by urine retention, you may need a catheter to drain urine from the bladder.

Getting support for urinary problems

Urinary problems might affect how you feel about yourself and your sense of independence. If you are finding them hard to deal with, speak to your doctor or nurse.

Bowel problems

You might get bowel problems if your prostate cancer has spread to your bowel, although this isn’t very common. If you have bowel problems, these are more likely to be caused by previous radiotherapy to your prostate, or by some medications.

Bowel problems can include:

- passing more wind than usual, which may sometimes be wet (flatulence)

- passing loose and watery bowel movements (diarrhoea)

- difficulty emptying your bowels (constipation) or a feeling that your bowels haven’t emptied properly

- needing to empty your bowel more often, or having to rush to the toilet (faecal urgency)

- pain in your abdomen (stomach area) or back passage

- being unable to empty your bowels (bowel blockage)

- leaking from your back passage (faecal urgency) – this is very rare.

Speak to your doctor or nurse if you have any of these symptoms. There are treatments available that may help.

Men with advanced prostate cancer can get bowel problems for a variety of reasons. Radiotherapy to the prostate and surrounding area can cause bowel problems. You might get these during treatment, or they can develop months or years later.

Pain-relieving drugs such as morphine and codeine can cause constipation. Don’t stop taking them, but speak to your doctor or nurse if you have any problems.

Becoming less active, changes to your diet, and not drinking enough fluids can also cause constipation.

You may also get bowel problems if prostate cancer spreads to your lower bowel (rectum), but this isn’t common. If it happens, it can cause symptoms including constipation, pain, bleeding and, rarely, being unable to empty your bowels.

Problems emptying your bowels or leaking from your back passage might sometimes be caused by a condition called metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC). But this is rare.

What can help?

Lifestyle changes

Speak to your doctor or nurse about whether changing your diet could help with these problems. They may refer you to a dietitian, who can help you make changes to your diet.

If you have constipation, eating lots of high fibre foods can help. These include fruit such as prunes, wholemeal bread, wholegrain breakfast cereals and porridge. Drink plenty of water. Aim for about two litres (eight glasses) of water a day. Gentle exercise such as going for a walk can also help with constipation.

If you have diarrhoea, eating less fibre for a short time may help, although the evidence for this isn’t very strong. Low fibre foods include white rice, pasta and bread, potatoes without the skins, cornmeal, eggs and lean white meat. Avoiding spicy food and eating fewer dairy products, such as milk and cheese, may also help. Make sure you drink lots of water to replace the liquid your body is losing.

Read more about maintaining a healthy diet.

Medicines or treatments

If you have constipation, your doctor or nurse may prescribe laxatives to help you empty your bowels. If you have constipation or bowel obstruction caused by prostate cancer, they might recommend radiotherapy to the bowel. If your bowel becomes very blocked, you may need to have surgery. But this is rare.

Information and support

Bowel problems can be distressing and difficult to talk about. But health professionals are used to discussing these problems and can help you find ways to deal with them. You could also ask your GP to refer you to an NHS continence service. Their specialist nurses can give you support and information on products that can help.

Macmillan Cancer Support has more information about coping with bowel problems.

Broken bones (fractures)

The most common place for prostate cancer to spread to is the bones. The cancer can damage bones, making them weaker. And some types of hormone therapy can also make your bones weaker. You might hear this called bone thinning. If bone thinning is severe, it can lead to a condition called osteoporosis. This can increase your risk of broken bones (fractures). Read more about bone thinning and hormone therapy.

Damage to the bones can make it difficult or painful to move around. You may not be able to do some of the things that you used to do because you’re in pain, or because you might be more likely to break a bone. This can be hard to accept.

What can help?

You might be given radiotherapy to slow down the growth of the cancer. This can help control damage to the bones and relieve bone pain. Read more about radiotherapy for advanced prostate cancer.

Your doctor may offer you drugs called bisphosphonates. These can strengthen the bones and help prevent broken bones. Bisphosphonates can also be used to treat pain caused by cancer that has spread to the bones.

If an area of bone is badly damaged, you may be able to have surgery. A metal pin or plate is put inside the bone to strengthen it and reduce the risk of it breaking. Or, a type of cement can be used to fill the damaged area. Surgery isn’t suitable for all men with advanced prostate cancer. This will depend on where the damaged bone is, and other things such as whether you are well enough for surgery. If you have an operation, you may have radiotherapy afterwards to help stop the cancer growing in that area.

Even though you may not be able to do some physical activities, staying active can help with your general health and your ability to move around. It could also help to keep you strong and prevent falls that could cause broken bones. Speak to your doctor, nurse or physiotherapist about what you can and can’t do.

Read more about fragile bones on The Royal Osteoporosis Society website.

Sexual problems

Dealing with advanced prostate cancer can have an impact on your sex life. There are lots of different reasons why this might happen. For example, hormone therapy can reduce your desire for sex (your libido) and affect your ability to get or keep an erection. Other treatments that you may have had in the past, such as surgery or radiotherapy, can also cause erection problems. Feeling low, anxious or tired can affect your sex life too.

What can help?

People with prostate cancer can get free medical treatment and support for sexual problems on the NHS.

Treatments for erection problems include tablets, vacuum pump, injections, pellets and cream. Because getting an erection also relies on your thoughts and feelings, tackling any worries or relationship issues as well as having medical treatment can help. Speak to your GP, nurse or hospital doctor to find out more. They can offer you treatment or refer you to a specialist service.

When you’re on hormone therapy and have lost your desire for sex (libido), this might not come back. Some treatments may still help with your erections, even if your sex drive is low.

If you’re on long-term hormone therapy, you may be able to have intermittent hormone therapy. This is where you stop hormone therapy when the level of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in your blood is low and steady, and start it again if your PSA rises. PSA is a protein produced by normal cells in the prostate and also by prostate cancer cells. Your sex drive may improve while you’re not having hormone therapy. But it can take several months and some men don’t notice any improvement.

If you had sex before you were diagnosed with prostate cancer, your sex life is unlikely to be the same now. You may need some support dealing with these changes. There are still many ways to have pleasure, closeness and fun. If you have a partner, talking about sex, your thoughts and feelings can help you both deal with any changes. If you are in a relationship you may need time alone together, whatever your situation. If you are in a hospital, hospice or have carers coming to your house, make sure they know when you need some private time together.

If you have a catheter to help manage urinary problems, it is still possible to have sex. Speak to your nurse about this.

Lymphoedema

If the cancer spreads to the lymph nodes it could lead to a condition called lymphoedema – caused by a blockage in the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is part of your body’s immune system. It carries fluid called lymph around your body. If it is blocked, the fluid can build up and cause swelling (lymphoedema). Prostate cancer itself, as well as some treatments such as surgery or radiotherapy, can cause the blockage. This can happen months or even years after treatment.

Lymphoedema in prostate cancer usually affects the legs, but it can affect other areas, including the penis or scrotum (the skin around your testicles). Symptoms in the affected area can include:

- swelling

- pain, discomfort or heaviness

- inflammation, redness or infection

- tight or sore skin.

Lymphoedema can affect your daily life. You might be less able to move around and find it harder to carry out everyday tasks. Some men worry about how the affected area looks and feel anxious about other people seeing it.

What can help?

Speak to your nurse or GP if you have any symptoms. There are treatments that can help to manage them. Treatments aim to reduce or stop the swelling and make you more comfortable. They are most effective if you start them when you first get symptoms. If you have lymphoedema, you may be referred to a specialist lymphoedema nurse, who can show you how to manage the swelling. They are often based in hospices.

There are a variety of things that might help.

- Caring for the skin, such as regular cleaning and moisturising, can help to keep your skin soft and reduce the chance of it becoming cracked and infected.

- Special massage (manual lymphatic drainage) can help to increase the flow of lymph. Your nurse might be able to show you or a partner, family member or friend how to do this.

- Gentle exercise may help to improve the flow of lymph from the affected area of the body. For example, doing simple leg movements, similar to those recommended for long flights, may help with leg lymphoedema.

- Using compression bandages or stockings can help to encourage the lymph to drain from the affected area. Your nurse will show you how to use them.

- Wearing close-fitting underwear or lycra cycling shorts may help control any swelling in your penis or scrotum.

- Try to maintain a healthy weight as being overweight can make lymphoedema harder to manage. Read more about diet and physical activity.

Living with lymphoedema can be difficult. If you need support, speak to your nurse or GP. You could also refer yourself to an NHS counsellor to help you deal with how you’re feeling.

Macmillan Cancer Support and the Lymphoedema Support Network provide more information and can put you in touch with local support groups.

Anaemia

Some men with advanced prostate cancer develop a condition called anaemia. This is caused by a drop in the number of red blood cells, which means your blood doesn’t carry enough oxygen around the body. Anaemia can happen when your bone marrow is damaged – either by the prostate cancer or by treatment such as hormone therapy, chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Symptoms include feeling tired or weak, being out of breath and looking pale.

Sometimes anaemia is caused by not enough iron in your diet. You might be more at risk of this if you have problems eating.

What can help?

Speak to your doctor or nurse if you have symptoms of anaemia. You will have a blood test to check your red blood cell levels. Which treatment you’re offered will depend on what’s causing your anaemia.

Your doctor may recommend you take iron supplements to help with anaemia. These can cause bowel problems such as constipation or diarrhoea – see above for ways to manage this. If your red blood cell levels are very low, you may need a blood transfusion. This can be a quick and effective way of treating anaemia.

Macmillan Cancer Support and Cancer Research UK have more information about anaemia and blood transfusions.

Metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC)

Metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) happens when cancer cells that have spread from the prostate grow in or near to the spine, and press on the spinal cord. MSCC isn’t common, but you need to be aware of the risk if your prostate cancer has spread to your bones or has a high risk of spreading to your bones. The risk of MSCC is highest if the cancer has already spread to the spine. Speak to your doctor or nurse for more information about your risk.

MSCC can cause any of the following symptoms.

- Pain or soreness in your lower, middle or upper back or neck. The pain may be severe or get worse over time. It might get worse when you cough, sneeze, lift or strain, go to the toilet, or lie down. It might get worse when you are lying down. It may wake you at night or stop you from sleeping.

- A narrow band of pain around your abdomen (stomach area) or chest that can move towards your lower back, buttocks or legs.

- Pain that moves down your arms or legs.

- Weakness or loss of control of your arms or legs, or difficulty standing or walking. You might feel unsteady on your feet or feel as if your legs are giving way. Some people say they feel clumsy.

- Numbness or tingling (pins and needles) in your legs, arms, fingers, toes, buttocks, stomach area or chest, that doesn’t go away.

- Problems controlling your bladder or bowel. You might not be able to empty your bladder or bowel, or you might have no control over emptying them.

These symptoms can also be caused by other conditions, but it’s still important to get medical advice straight away in case you do have MSCC. If your doctor or nurse isn’t available, go to your nearest accident and emergency (A&E) department.

Don’t wait

It is very important to seek medical advice immediately if you think you might have MSCC.

Don’t wait to see if it gets better and don’t worry if it’s an inconvenient time, such as the evening or weekend. If you are diagnosed with MSCC, you should start treatment as soon as possible – ideally within 24 hours. MSCC could affect your ability to walk and move around if it isn’t treated quickly. Getting treatment early can reduce the risk of long-term problems.

Hypercalcaemia

Hypercalcaemia is a high level of calcium in your blood. Calcium is usually stored in the bones, but the cancer can cause calcium to leak into the blood. It is very rare, but can sometimes affect men with advanced prostate cancer. If it happens, it’s important to treat it so that you don’t develop a more serious condition.

Hypercalcaemia doesn’t always cause symptoms, but it can cause:

- bone pain

- tiredness, weakness or lack of energy

- loss of appetite

- difficulty emptying your bowels (constipation)

- confusion

- feeling and being sick (nausea and vomiting)

- pain in your lower stomach area

- feeling more thirsty than usual

- needing to urinate often (frequency).

These symptoms can be quite common in men with advanced prostate cancer and might not be caused by hypercalcaemia. Tell your doctor or nurse if you have any of these symptoms. They may do some tests to find out what is causing them, including a blood test to check the level of calcium in your blood.

What can help?

You may have to go into hospital or a hospice for a couple of days. You will be given fluid through a drip in your arm. This will help to flush calcium out of your blood and bring your calcium levels down.

Drugs called bisphosphonates can help treat hypercalcaemia by lowering the level of calcium in your blood. They usually start to work in two to four days. If your blood calcium levels are still high, you may be given another dose of bisphosphonates after a week. You’ll usually stop treatment once your calcium levels are back to normal.

Once your calcium levels are back to normal, you’ll have regular blood tests to check your calcium levels stay low. Tell your doctor or nurse if your symptoms come back.

Cancer Research UK has more information about hypercalcaemia.

Eating problems and weight loss

Some men with advanced prostate cancer have problems eating, or don’t feel very hungry. You might feel or be sick. These problems may be caused by your cancer or by your treatments. Being worried about things can also affect your appetite.

Problems eating or loss of appetite can lead to weight loss and can make you feel very tired and weak. Advanced prostate cancer can also cause weight loss by changing the way your body uses energy.

What can help?

If you feel sick because of your treatment, your doctor can give you anti-sickness drugs. Steroids can also increase your appetite and are sometimes given along with other treatments.

Try to eat small amounts often. If you’re struggling to eat because of nausea (feeling sick), try to avoid strong smelling foods. Cold foods tend to smell less, or it may help if someone cooks for you. Try to eat when you feel less sick, even if it’s not your usual mealtime. Fatty and fried foods can make sickness worse. Drink plenty of water, but drink slowly and try not to drink too much before you eat.

Tell your doctor if you lose weight. They can refer you to a dietitian who can provide advice about high calorie foods and any supplements that might help. It can be upsetting for your family to see you losing weight, and they may also need support. Macmillan Cancer Support and Marie Curie provide support and information about eating problems in advanced cancer.

What treatments can I have?

Men with advanced prostate cancer may be offered different treatments to help with different things. Some treatments aim to keep the cancer under control, while others aim to help manage symptoms caused by the cancer.

Treatments to control advanced prostate cancer

If you’ve just been diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer, you may be offered the following treatments:

- chemotherapy with hormone therapy

- hormone therapy alone

- clinical trials.

Chemotherapy with hormone therapy

Chemotherapy uses anti-cancer drugs to kill cancer cells, wherever they are in the body. It won’t get rid of your prostate cancer, but it aims to shrink it and slow down its growth. You might be offered chemotherapy at the same time as, or soon after, you start having hormone therapy. This helps many men to live longer, and may help delay symptoms such as pain.

You need to be quite fit to have chemotherapy. This is because it can cause side effects that are harder to deal with if you have other health problems. Read more about chemotherapy.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy will be a life-long treatment for most men with advanced prostate cancer.

Prostate cancer usually needs the hormone testosterone to grow. Hormone therapy works by either stopping your body from making testosterone, or stopping testosterone from reaching the cancer cells. This usually causes the cancer to shrink, wherever it is in the body. Hormone therapy can also help control symptoms of advanced prostate cancer, such as bone pain.

Hormone therapy can cause side effects – speak to your doctor or nurse about ways to manage these. Read more about hormone therapy, and its side effects.

Clinical trials

There are clinical trials looking at new treatments for men with advanced prostate cancer and new ways to use existing treatments. Clinical trials aren’t suitable for everyone and there may not be any in your area. You can ask your doctor or nurse if there are any trials you could take part in, or speak to our Specialist Nurses. Read more about clinical trials.

Radiotherapy to the prostate

Some men who have just been diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer may be offered external beam radiotherapy as part of their first treatment. This is where high-energy X-ray beams are directed at the prostate from outside the body. The X-ray beams damage the cancer cells and stop them from dividing and growing. Read more about radiotherapy for advanced prostate cancer.

Radiotherapy to the prostate isn’t suitable for all men with advanced prostate cancer. If it isn’t suitable for you, you might be offered a type of radiotherapy to help manage symptoms instead.

Further treatments to control the cancer

Your first treatment may help keep your cancer under control. But over time, the cancer may change and start to grow again. If this happens you might be offered other treatments, including:

- more hormone therapy

- more chemotherapy

- radium-223 (Xofigo®)

- clinical trials

More hormone therapy

Your prostate cancer may respond well to other types of hormone therapy, such as abiraterone (Zytiga®), enzalutamide (Xtandi®), steroids or oestrogens, or to a combination of treatments.

More chemotherapy

If you’ve had hormone therapy on its own as a first treatment, you might be offered a chemotherapy drug called docetaxel (Taxotere®). This may help some men to live longer, and can help to improve and delay symptoms. If you’ve already had docetaxel, you might be offered more docetaxel or another chemotherapy drug called cabazitaxel (Jevtana®).

Radium-223 (Xofigo®)

This is a type of internal radiotherapy that may be an option if your cancer has spread to your bones and is causing pain. A radioactive liquid is injected into your arm and collects in bones that have been damaged by the cancer. It kills cancer cells in the bones and helps some men to live longer. It can also help to reduce bone pain and delay some symptoms, such as bone fractures. Read more about radiotherapy for advanced prostate cancer.

Treatments to help manage symptoms

Treatments to help manage symptoms caused by advanced prostate cancer include:

- pain-relieving drugs

- radiotherapy

- bisphosphonates

- complementary therapies

Pain-relieving drugs

There are lots of different types of pain-relieving drugs, such as tablets, patches and injections. Your doctor or palliative care nurse will help you find what’s best for you.

Some men worry about becoming addicted to pain-relieving drugs. But this is uncommon in men with prostate cancer. Read more about managing pain in advanced prostate cancer.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy can help control symptoms by slowing down the growth of the cancer. Radiotherapy to help control symptoms is sometimes called palliative radiotherapy.

The most common type of radiotherapy used to reduce symptoms is external beam radiotherapy. This is high-energy X-ray beams targeted at the area being treated from outside the body. It can help to manage symptoms such as pain, blood in your urine or discomfort from swollen lymph nodes. It’s also used to treat metastatic spinal cord compression.

You might have slightly more pain during treatment, and for a few days afterwards, but this should soon get better. It can take a few weeks for radiotherapy to have its full effect.

If your prostate cancer is causing bone pain, you may be offered radium-223 to help reduce the pain and delay some other symptoms.

Read more about radiotherapy for advanced prostate cancer.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are drugs that are sometimes used to help strengthen bones that have become weak or thin. This may be caused by cancer that has spread, but can also happen if you’re having hormone therapy. Bisphosphonates can also be used to treat bone pain if other pain-relieving treatments aren’t helping, or to treat hypercalcaemia. Read more about bisphosphonates.

Complementary therapies

Complementary therapies may be used alongside medical treatment. They include acupuncture, massage, yoga, meditation, reflexology and hypnotherapy. Some people find they help them deal with cancer symptoms and side effects of treatment, such as tiredness or hot flushes. But the evidence for most complementary therapies isn’t very strong.

Some complementary therapies have side effects or may interfere with your cancer treatment. So make sure your doctor or nurse knows about any complementary therapies you’re using or thinking of trying. And make sure that any complementary therapist you see knows about your cancer and treatments.

Some complementary therapies are available through hospices, GPs and hospitals. But if you want to find a therapist yourself, make sure they are properly qualified and belong to a professional body. The Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council have advice about finding a therapist.

Macmillan Cancer Support and Cancer Research UK have more information about different therapies and important safety issues to think about when choosing a therapy.

The specialist palliative care team worked out what I needed and recommended treatments to reduce my pain.

Health and social care professionals you might see

You might see a range of different professionals to help manage your symptoms and offer emotional and practical support. Some may have been treating you since your diagnosis. Others provide specific services or specialise in providing treatment to manage symptoms (palliative care).

If you have questions or concerns at any time, speak to someone in your medical team. They can explain your diagnosis, treatment and side effects, listen to your concerns, and help you get support.

Your multi-disciplinary team (MDT)

This is the team of health professionals involved in your care. Your MDT is likely to include the following:

- Specialist nurse. This is a nurse who specialises in caring for men with prostate cancer. You may also hear them called a urology nurse specialist or a clinical nurse specialist (CNS). They provide care and advice, and can offer emotional support and practical information.

- Urologist. This is a surgeon who specialises in treating problems with the urinary system, which includes the prostate.

- Oncologist. This is a doctor who specialises in treating cancer using treatments other than surgery, including radiotherapy, hormone therapy and chemotherapy.

- Therapeutic or specialist radiographer. This is a health professional who plans and gives radiotherapy. They may also do follow-up checks to see how well the treatment has worked.

Read more about people in your MDT.

Your GP, practice nurse and district nurse

Your GP, practice nurse, and district or community nurse will work with other health professionals to co-ordinate your care and offer you support and advice. They can also refer you to local services. They can visit you in your home and also help support your family. They might also care for you if you go into a nursing home or hospice.

Palliative care team

This includes specialist doctors and nurses who provide treatment to manage pain and other symptoms of advanced cancer. You might hear this called symptom control or supportive care. They also provide emotional, physical, practical and spiritual support for you and your family. They work in hospitals and hospices, and they might be able to visit you at home. Your hospital doctor, nurse or GP can refer you to a palliative care team. Read more about palliative care.

Palliative care can be provided at any stage of advanced prostate cancer and isn’t just for men in the final stages of life. Men with advanced prostate cancer might have palliative care for many months or years.

People who work in palliative care include the following.

- Palliative care nurses. You might hear your palliative care nurse called a Macmillan nurse. But not all palliative care nurses are Macmillan nurses. This will depend on your local services. For example, in some areas palliative care nurses are funded by a local hospice, rather than by Macmillan.

- Marie Curie nurses. Marie Curie nurses provide care, practical advice and emotional support to people in the last few months or weeks of life. They visit people at home and can provide care overnight if you need it. Your district nurse might be able to arrange a Marie Curie nurse for you. Services vary depending on where you live. In some areas, a hospice may provide this care rather than Marie Curie nurses.

Hospices

Hospices provide a range of services for men with advanced prostate cancer, and their family and friends. They can provide treatment to manage symptoms as well as emotional, spiritual, psychological, practical and social support.

Hospices don’t just provide care for people at the end of their life. Some people go into a hospice for a short time to get their symptoms under control, then go home again. For example, they might give you drugs called bisphosphonates if you have hypercalcaemia, or a blood transfusion if you have anaemia.

Most hospices have nurses who can visit you at home, and some provide day care. This means you can use their services while still living at home.

Hospice care is free for patients and the people looking after them. Most hospices are happy to tell you about the services they provide and show you around. Read more about hospice care.

Your GP, hospital doctor or district nurse can refer you to a hospice service. Find out more about services in your area from Hospice UK.

Hospitals

Many men with advanced prostate cancer will need to stay in hospital at some point. Some men decide to go into hospital to help get their symptoms under control. Other men have to go into hospital if their symptoms suddenly get worse. This can be distressing or upsetting, but it may be the best way to get the care you need. If you’re admitted to hospital, this may just be for a few days or it might be for longer.

Other professionals who can help

Your doctor, nurse or GP can refer you to these professionals.

- Physiotherapists can help with mobility and provide exercises to help improve fitness or ease pain. This can help you stay independent for longer.

- Counsellors, psychologists or psychotherapists can help you and your family work through any difficult feelings and find ways of coping. Many hospitals have counsellors or psychologists who specialise in helping people with cancer. You can also get free counselling on the NHS without a referral from your GP. Go to nhs.uk/counselling to find out more.

- Dietitians can give you advice about healthy eating, which might help with fatigue and staying a healthy weight. They can also help if you are losing weight or having problems eating.

- Occupational therapists can provide advice and access to equipment and adaptations to help with daily life. For example, help with dressing, eating, bathing or using the stairs.

- Social services, including social workers, can provide practical and financial advice and access to emotional support. They can give you advice about practical issues such as arranging for someone to support you at home. What’s available varies from place to place. Your GP, hospital doctor or nurse might be able to refer you to some services. The telephone number for your local social service department will be in the phonebook under the name of your local authority, on their website and at the town hall.

References

Updated: November 2021 | Due for Review: November 2023

- Mottet N, Van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Cornford P, De Santis M, Fanti S, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. European Association of Urology; 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline 131. 2019.

- Drudge-Coates L, Oh WK, Tombal B, Delacruz A, Tomlinson B, Ripley AV, et al. Recognizing Symptom Burden in Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Global Patient and Caregiver Survey. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 Apr;16(2):e411–9.

- Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer 5 year survival by stage. 2014.

- James ND, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Dearnaley DP, De Bono JS, Gale J, et al. Survival with Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the “Docetaxel Era”: Data from 917 Patients in the Control Arm of the STAMPEDE Trial (MRC PR08, CRUK/06/019). Eur Urol. 2015 Jun;67(6):1028–38.

- Koornstra RHT, Peters M, Donofrio S, van den Borne B, de Jong FA. Management of fatigue in patients with cancer – A practical overview. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014 Jul;40(6):791–9.

- Pachman DR, Price KA, Carey EC. Nonpharmacologic approach to fatigue in patients with cancer. Cancer J. 2014;20(5):313–318.

- Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, Breitbart W, Escalante CP, Ganz PA, et al. Screening, Assessment, and Management of Fatigue in Adult Survivors of Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jun 10;32(17):1840–50.

- Langston B, Armes J, Levy A, Tidey E, Ream E. The prevalence and severity of fatigue in men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2013 Jun;21(6):1761–71.

- Horneber M, Fischer I, Dimeo F, Ruffer JU, Weis J. Cancer-Related Fatigue. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012 Mar;109(9):161–71.

- Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-Related Fatigue: The Scale of the Problem. The Oncologist. 2007 May 1;12(suppl_1):4–10.

- Morrow GR. Cancer-Related Fatigue: Causes, Consequences, and Management. The Oncologist. 2007 May 1;12(suppl_1):1–3.

- Storey DJ, McLaren DB, Atkinson MA, Butcher I, Frew LC, Smyth JF, et al. Clinically relevant fatigue in men with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer on long-term androgen deprivation therapy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(6):1542–9.

- Storey DJ, McLaren DB, Atkinson MA, Butcher I, Liggatt S, O’Dea R, et al. Clinically relevant fatigue in recurrence-free prostate cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2012 Jan 1;23(1):65–72.

- Merriman JD, Dodd M, Lee K, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Aouizerat BE, et al. Differences in Self-reported Attentional Fatigue Between Patients With Breast and Prostate Cancer at the Initiation of Radiation Therapy: Cancer Nurs. 2011 Sep;34(5):345–53.

- Larkin D, Lopez V, Aromataris E. Managing cancer-related fatigue in men with prostate cancer: A systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions. Int J Nurs Pract. 2014 Oct;20(5):549–60.

- Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014 Aug 12;11(10):597–609.

- Ryan J, Carroll J, Ryan E, Mustian K, Fiscella K, Morrow G. Mechanisms of Cancer-Related Fatigue. The Oncologist. 2007 May;12:22–34.

- Wang XS. Pathophysiology of Cancer-Related Fatigue. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008 Jan 1;12(0):11–20.

- Kyrdalen AE, Dahl AA, Hernes E, Cvancarova M, Foss\aa SD. Fatigue in hormone-naive prostate cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy or definitive radiotherapy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010;13(2):144–150.

- Minton O, Jo F, Jane M. The role of behavioural modification and exercise in the management of cancer-related fatigue to reduce its impact during and after cancer treatment. Acta Oncol. 2015 May;54(5):581–6.

- Garrett K, Dhruva A, Koetters T, West C, Paul SM, Dunn LB, et al. Differences in Sleep Disturbance and Fatigue Between Patients with Breast and Prostate Cancer at the Initiation of Radiation Therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011 Aug;42(2):239–50.

- Gardner JR, Livingston PM, Fraser SF. Effects of Exercise on Treatment-Related Adverse Effects for Patients With Prostate Cancer Receiving Androgen-Deprivation Therapy: A Systematic Review. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Feb 1;32(4):335–46.

- Keogh JWL, MacLeod RD. Body Composition, Physical Fitness, Functional Performance, Quality of Life, and Fatigue Benefits of Exercise for Prostate Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 Jan;43(1):96–110.

- Bourke L, Smith D, Steed L, Hooper R, Carter A, Catto J, et al. Exercise for Men with Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2016 Apr;69(4):693–703.

- Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2012 Nov 14; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub3

- Teleni L, Chan RJ, Chan A, Isenring EA, Vela I, Inder WJ, et al. Exercise improves quality of life in androgen deprivation therapy-treated prostate cancer: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016 Jan 2;23(2):101–12.

- Menichetti J, Villa S, Magnani T, Avuzzi B, Bosetti D, Marenghi C, et al. Lifestyle interventions to improve the quality of life of men with prostate cancer: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016 Dec;108:13–22.

- Nguyen PL, Alibhai SMH, Basaria S, D’Amico AV, Kantoff PW, Keating NL, et al. Adverse Effects of Androgen Deprivation Therapy and Strategies to Mitigate Them. Eur Urol. 2015 May;67(5):825–36.

- Thompson JC, Wood J, Feuer D. Prostate cancer: palliative care and pain relief. Br Med Bull. 2007;83:341–54.

- Kane C, Hoskin P, Bennett M. Cancer induced bone pain (clinical review). BMJ. 2015;350(h315).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings. NICE Clinical Guideline 173. (updated April 2018); 2013.

- Parsons BA, Evans S, Wright MP. Prostate cancer and urinary incontinence. Maturitas. 2009;63(4):323–8.

- Yoon PD, Chalasani V, Woo HH. Systematic review and meta-analysis on management of acute urinary retention. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015 Dec;18(4):297–302.

- Gravas S, Cornu JN, Gacci M, Gratzke C, Herrmann TRW, Mamoulakis C, et al. EAU Guidelines on Management of Non-Neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), incl. Benign Prostatic Obstruction (BPO). European Association of Urology; 2019.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: assessment and management. NICE Clinical Guideline 97 [Internet]. (modified June 2015); 2010. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg97

- Alsadius D, Olsson C, Pettersson N, Tucker SL, Wilderäng U, Steineck G. Patient-reported gastrointestinal symptoms among long-term survivors after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014 Aug;112(2):237–43.

- Schaake W, Wiegman EM, de Groot M, van der Laan HP, van der Schans CP, van den Bergh ACM, et al. The impact of gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity on health related quality of life among irradiated prostate cancer patients. Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2014 Feb;110(2):284–90.

- Shadad AK, Sullivan FJ, Martin JD, Egan LJ. Gastrointestinal radiation injury: Symptoms, risk factors and mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2013 Jan 14;19(2):185–98.

- Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, Bosch W, Bruner DW, Bahary J-P, et al. Effect of Standard vs Dose-Escalated Radiation Therapy for Patients With Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer: The NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Jun 1;4(6):e180039–e180039.

- Clarke NW. Management of the Spectrum of Hormone Refractory Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2006 Sep;50(3):428–39.

- Andreyev HJN. GI Consequences of Cancer Treatment: A Clinical Perspective. Radiat Res. 2016 Mar 28;185(4):341–8.

- Aluwini S, Pos F, Schimmel E, Krol S, van der Toorn PP, de Jager H, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):464–74.

- Berkey FJ. Managing the adverse effects of radiation therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2010 Aug 15;82(4):381–8, 394.

- Bubendorf L, Schöpfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, et al. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: An autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000 May;31(5):578–83.

- Pettersson A, Johansson B, Persson C, Berglund A, Turesson I. Effects of a dietary intervention on acute gastrointestinal side effects and other aspects of health-related quality of life: A randomized controlled trial in prostate cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2012 Jun;103(3):333–40.

- Henson CC, Burden S, Davidson SE, Lal S. Nutritional interventions for reducing gastrointestinal toxicity in adults undergoing radical pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2014 Nov 18];(11). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009896.pub2

- Wedlake LJ, Shaw C, Whelan K, Andreyev HJN. Systematic review: the efficacy of nutritional interventions to counteract acute gastrointestinal toxicity during therapeutic pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013 Jun;37(11):1046–56.

- Eastham JA. Bone health in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007 Jan;177(1):17–24.

- Serpa Neto A, Tobias-Machado M, Esteves MAP, Senra MD, Wroclawski ML, Fonseca FLA, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy in patients under androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15(1):36–44.

- Patrick DL, Cleeland CS, von Moos R, Fallowfield L, Wei R, Öhrling K, et al. Pain outcomes in patients with bone metastases from advanced cancer: assessment and management with bone-targeting agents. Support Care Cancer [Internet]. 2014 Dec 23 [cited 2015 Feb 18]; Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-014-2525-4

- Macherey S, Monsef I, Jahn F, Jordan K, Yuen KK, Heidenreich A, et al. Bisphosphonates for advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2017 Dec 26 [cited 2018 Jan 5]; Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006250.pub2/abstract

- Attar S, Steffner RJ, Avedian R, Hussain WM. Surgical intervention of nonvertebral osseous metastasis. Cancer Control. 2012;19(2):113–121.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Percutaneous cementoplasty for palliative treatment of bony malignancies. IPG179. 2006;

- Bancroft J, Janssen E, Strong D, Carnes L, Vukadinovic Z, Long JS. The Relation Between Mood and Sexuality in Heterosexual Men. Arch Sex Behav. 2003 Jun 1;32(3):217–30.

- Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, Sui D, Neese L, Jenkins R, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012 Jan 15;118(2):500–9.

- Magnan S, Zarychanski R, Pilote L, Bernier L, Shemilt M, Vigneault E, et al. Intermittent vs Continuous Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2015 Sep 17;1–10.

- Botrel TEA, Clark O, dos Reis RB, Pompeo ACL, Ferreira U, Sadi MV, et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation for locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2014;14:9.

- Todd M. Understanding lymphoedema in advanced disease in a palliative care setting. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2009;15(10):474.

- Wanchai A, Beck M, Stewart BR, Armer JM. Management of Lymphedema for Cancer Patients With Complex Needs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013 Feb;29(1):61–5.

- Shaitelman SF, Cromwell KD, Rasmussen JC, Stout NL, Armer JM, Lasinski BB, et al. Recent progress in the treatment and prevention of cancer-related lymphedema. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015 Jan;65(1):55–81.

- Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. An Update on Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010 Dec;17(4):R305–15.

- Hicks BM, Klil-Drori AJ, Yin H, Campeau L, Azoulay L. Androgen Deprivation Therapy and the Risk of Anemia in Men with Prostate Cancer: Epidemiology. 2017 Sep;28(5):712–8.

- Curtis KK, Adam TJ, Chen S-C, Pruthi RK, Gornet MK. Anaemia following initiation of androgen deprivation therapy for metastatic prostate cancer: A retrospective chart review. Aging Male. 2008 Jan;11(4):157–61.

- Nalesnik JG, Mysliwiec AG, Canby-Hagino E. Anemia in men with advanced prostate cancer: incidence, etiology, and treatment. Rev Urol. 2004;6(1):1.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Metastatic spinal cord compression: Diagnosis and management of adults at risk of and with metastatic spinal cord compression. NICE clinical guideline 75 [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg75

- Loblaw DA, Mitera G, Ford M, Laperriere NJ. A 2011 updated systematic review and clinical practice guideline for the management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2012;84(2):312–7.

- Samphao S, Eremin JM, Eremin O. Oncological emergencies: clinical importance and principles of management. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19(6):707–13.

- Al-Qurainy R, Collis E. Metastatic spinal cord compression: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2016 May 19;353:i2539.

- Mundy GR, Roodman GD, Smith MR. New Opportunities for the Management of Cancer-Related Bone Complications. 2009 [cited 2013 Nov 4]; Available from: http://www.curatio-cme.com/newsletters/CAHO_New_Opp_May2009.pdf

- Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, Pirolli M, Quach D, Quigley JM, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016 Aug;5(8):2091–100.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypercalcaemia: Clinical Knowledge Summary [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2016 Oct 6]. Available from: http://cks.nice.org.uk/hypercalcaemia

- Walji N, Chan AK, Peake DR. Common acute oncological emergencies: diagnosis, investigation and management. Postgrad Med J. 2008 Aug 1;84(994):418–27.

- Dorff TB, Crawford ED. Management and challenges of corticosteroid therapy in men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013 Jan 1;24(1):31–8.

- NHS England. Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement: Docetaxel in combination with androgen deprivation therapy for the treatment of hormone naive metastatic prostate cancer. 2016.

- James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, Spears MR, et al. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016 Mar;387(10024):1163–77.

- Vale CL, Burdett S, Rydzewska LH, Albiges L, Clarke NW, Fisher D, et al. Addition of docetaxel or bisphosphonates to standard of care in men with localised or metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analyses of aggregate data. Lancet Oncol. 2015;

- Tucci M, Bertaglia V, Vignani F, Buttigliero C, Fiori C, Porpiglia F, et al. Addition of Docetaxel to Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Patients with Hormone-sensitive Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2015 Sep;

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Docetaxel for the treatment of hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. NICE technology appraisal guidance 101. 2006.

- Bahl A, Oudard S, Tombal B, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Kocak I, et al. Impact of cabazitaxel on 2-year survival and palliation of tumour-related pain in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated in the TROPIC trial. Ann Oncol. 2013 May 30;24(9):2402–8.

- Collins R, Trowman R, Norman G, Light K, Birtle A, Fenwick E, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of docetaxel and mitoxantrone for the treatment of metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006 Aug 1;95(4):457–62.

- Serpa Neto A, Tobias-Machado M, Kaliks R, Wroclawski ML, Pompeo ACL, Del Giglio A. Ten Years of Docetaxel-Based Therapies in Prostate Adenocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 2244 Patients in 12 Randomized Clinical Trials. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2011 Dec;9(2):115–23.

- Singer EA, Srinivasan R. Intravenous therapies for castration-resistant prostate cancer: Toxicities and adverse events. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2012 Jul;30(4):S15–9.

- de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels J-P, Kocak I, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1147–54.

- Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, Clarke NW, Hoyle AP, Ali A, et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2018 Oct;

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cabazitaxel for hormone-relapsed metastatic prostate cancer treated with docetaxel. Technology appraisal guidance 391. 2016.

- Scottish Medicines Consortium. Cabazitaxel, 60mg concentrate and solvent for solution for infusion (Jevtana®). SMC No.735/11. 2016.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Radium-223 dichloride for treating hormone-relapsed prostate cancer with bone metastases. Technology appraisal guidance 376. 2016.

- Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O’Sullivan JM, Fosså SD, et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213–23.

- Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, Helle SI, O’Sullivan JM, Fosså SD, et al. Alpha Emitter Radium-223 and Survival in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213–23.

- British Pain Society. Cancer pain management: a perspective from the British Pain Society, supported by the Association for Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners. London: British Pain Soc.; 2010.

- Li KK, Hadi S, Kirou-Mauro A, Chow E. When Should we Define the Response Rates in the Treatment of Bone Metastases by Palliative Radiotherapy? Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb;20(1):83–9.

- Spencer K, Parrish R, Barton R, Henry A. Palliative radiotherapy. BMJ. 2018 Mar 23;k821.

- Hospice UK. What is hospice care? 2011.

- National Institute for Health Research. Better Endings: Right care, right place, right time. [Internet]. 2015. Available from: http://www.dc.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/file/0005/157037/Better-endings-FINAL-DH-single-page.pdf

- NHS National End of Life Care Programme. Deaths from urological cancers in England 2001-2010 [Internet]. 2012 Nov. Available from: http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications/deaths_from_urological_cancers

- Husson O, Mols F, Poll-Franse LV van de. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010 Sep 24;mdq413.

- Saylor PJ, Smith MR. Metabolic Complications of Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. J Urol. 2013 Jan;189(1):S34–44.

- Allott EH, Masko EM, Freedland SJ. Obesity and Prostate Cancer: Weighing the Evidence. Eur Urol. 2013 May;63(5):800–9.

- Keto CJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC, Kane CJ, Amling CL, et al. Obesity is associated with castration-resistant disease and metastasis in men treated with androgen deprivation therapy after radical prostatectomy: results from the SEARCH database. BJU Int. 2011;110(4):492–8.

- De Laet C, Kanis JA, Odén A, Johanson H, Johnell O, Delmas P, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2005 Nov;16(11):1330–8.

- Oefelein MG, Ricchuiti V, Conrad W, Seftel A, Bodner D, Goldman H, et al. Skeletal fracture associated with androgen suppression induced osteoporosis: the clinical incidence and risk factors for patients with prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;166(5):1724–1728.

- Ryan CW, Huo D, Stallings JW, Davis RL, Beer TM, McWhorter LT. Lifestyle Factors and Duration of Androgen Deprivation Affect Bone Mineral Density of Patients with Prostate Cancer During First Year of Therapy. Urology. 2007 Jul;70(1):122–6.

- Abrahamsen B, Brask-Lindemann D, Rubin KH, Schwarz P. A review of lifestyle, smoking and other modifiable risk factors for osteoporotic fractures. BoneKEy Rep. 2014 Sep 3;3:574.

- Hechtman LM. Clinical Naturopathic Medicine [Internet]. Harcourt Publishers Group (Australia); 2014 [cited 2015 Jul 21]. 1610 p. Available from: http://www.bookdepository.com/Clinical-Naturopathic-Medicine-Leah-Hechtman/9780729541923

- Tillisch K. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2006 May 1;55(5):593–6.

- NHS Choices. The risks of drinking too much [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Jul 4]. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/alcohol/Pages/Effectsofalcohol.aspx

- Islami F, Moreira DM, Boffetta P, Freedland SJ. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Tobacco Use and Prostate Cancer Mortality and Incidence in Prospective Cohort Studies. Eur Urol. 2014 Dec;66(6):1054–64.

- Moreira DM, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Cooperberg MR, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with an increased risk of biochemical disease recurrence, metastasis, castration-resistant prostate cancer, and mortality after radical prostatectomy: Results from the SEARCH database. Cancer. 2014 Jan 15;120(2):197–204.

- Davies NJ, Batehup L, Thomas R. The role of diet and physical activity in breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer survivorship: a review of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2011 Nov 8;105:S52–73.

- Ahmadi H, Daneshmand S. Androgen deprivation therapy: evidence-based management of side effects. BJU Int. 2013 Apr;111(4):543–8.

- Hamilton K, Chambers SK, Legg M, Oliffe JL, Cormie P. Sexuality and exercise in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2015 Jan;23(1):133–42.

- Cormie P, Newton RU, Taaffe DR, Spry N, Joseph D, Hamid MA, et al. Exercise maintains sexual activity in men undergoing androgen suppression for prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16(2):170–175.

- Newby TA, Graff JN, Ganzini LK, McDonagh MS. Interventions that may reduce depressive symptoms among prostate cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2015 Dec;24(12):1686–93.

- Chipperfield K, Brooker J, Fletcher J, Burney S. The impact of physical activity on psychosocial outcomes in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: A systematic review. Health Psychol. 2014;33(11):1288–97.

- Keilani M, Hasenoehrl T, Baumann L, Ristl R, Schwarz M, Marhold M, et al. Effects of resistance exercise in prostate cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2017 Jun 10;

- Macmillan Cancer Support. Your rights at work [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2015 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Documents/Cancerinfo/Livingwithandaftercancer/WorkandcancerPDFs/Yourrightsatwork_2013_2.pdf

- nidirect. Employment rights and the Disability Discrimination Act. Available from: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/employment-rights-and-disability-discrimination-act

- Compassion in Dying. IN04 Your rights in Northern Ireland [Internet]. [cited 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.compassionindying.org.uk/sites/default/files/IN04%20Your%20rights%20in%20Northern%20Ireland.pdf

- Abel J, Pring A, Rich A, Malik T, Verne J. The impact of advance care planning of place of death, a hospice retrospective cohort study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2013;3(2):168–173.

- Watson M, Lucas C, Hoy A, Back I, Armstrong P. Palliative care adult network guidelines [Internet]. 4th Edition. 2016. Available from: http://book.pallcare.info/index.php?user_style=1

- Compassion in Dying. Advance Decisions (Living Wills): an introduction. 2015.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Care of dying adults in the last days of life. NICE Quality Standard 144 [Internet]. 2017. Available from: care-of-dying-adults-in-the-last-days-of-life-pdf-75545479508677.pdf

- Marie Curie Cancer Care. Difficult conversations with dying people and their families [Internet]. 2014. Available from: http://www2.mariecurie.org.uk/ImageVaultFiles/id_1956/cf_100/Difficult-Conversations_report.PDF

- National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. What we know now 2014 [Internet]. Public Health England; 2015. Available from: www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/view?rid=872

- NHS Choices. End of life care: Why plan ahead? [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Planners/end-of-life-care/Pages/why-plan-ahead.aspx

- Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The supportive care needs of men with advanced prostate cancer. In: Oncology nursing forum [Internet]. Onc Nurs Society; 2011 [cited 2014 Dec 11]. p. 189–198. Available from: http://ons.metapress.com/index/G82215H56920T680.pdf

- NHS Choices. End of life care: What it involves and when it starts [Internet]. National Health Service. 2015 [cited 2018 Jan 24]. Available from: http://www.nhs.uk/Planners/end-of-life-care/Pages/what-it-involves-and-when-it-starts.aspx