Prostatitis treatments

Treatments for prostatitis

The treatments you’re offered will depend on the type of prostatitis you’re diagnosed with.

Each man will respond to the treatments differently. If one thing doesn’t work, you should be able to try something else, and there are things you can try to help yourself.

If your symptoms are not improving with the treatment offered by your GP, ask them to refer you to a urologist who specialises in managing prostatitis.

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS)

How is it treated?

Treatment varies from man to man – just like CPPS does. The treatments will help to control your symptoms and might even get rid of your CPPS completely. But CPPS could return weeks, months or even years later. You may have to try a few things until you find something that works well for you. You’ll probably try more than one of the following:

- medicines

- counselling

- exercises and physical activity

- treatment for pain

- other treatments.

Each person will respond to treatments differently. If one doesn’t work, you should be able to try something else. Your treatment may be managed by your GP or by a urologist at the hospital. You may also see a specialist nurse, or a sexual health specialist.

Medicines

There is some evidence that certain medicines can help improve prostatitis symptoms. Your GP or urologist may prescribe one or a combination of the following medicines.

- Alpha-blockers. There is some evidence that alpha-blockers, such as tamsulosin (Flomaxtra®, Diffundox®, Flomax Relief®, Pinexel®, Stronazon®), help improve urinary symptoms for some men, particularly a weak or slow flow, and pain. If they aren’t helping after four to six weeks, you will usually stop taking them.

- Antibiotics. Even though CPPS isn’t usually caused by a bacterial infection, there is a little evidence that antibiotics might help control symptoms in some men. This might be because they treat an infection that hasn’t been found by the tests. Or it might be because they help reduce inflammation.

- 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Although there is no strong evidence that 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, such as finasteride (generic finasteride or Proscar®), are effective, some men find they improve urinary symptoms. This could be because they shrink the prostate. They can take up to six months to work.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). There is no strong evidence that NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, are effective, but some men find they reduce symptoms such as pain. You can get some NSAIDs from pharmacies, but it’s important to talk to your GP first. This is because they can have side effects, such as stomach irritation and stomach ulcers.

- Pain-relieving medicines. These may help with any discomfort or pain. It may be enough to take over-the-counter pain relief such as paracetamol. Your doctor or a pharmacist can recommend ones that are suitable for you.

- Other medicines to relieve pain. Medicines used for other conditions can also be used to treat prostatitis pain. You might be offered anti-depressants (such as amitriptyline) to treat long-term prostatitis pain – some men with prostatitis find these helpful.

All medicines carry a risk of side effects. Ask your doctor for more information about the different treatments, and whether they might be suitable for you.

Names of medicines

Medicines often have two different names – a scientific or generic name and a brand name. For example, the alpha-blocker tablet tamsulosin is the scientific or generic name for the drug. Flomaxtra® and Diffundox® are examples of different brand names. The brand name is given to the drug by the company that makes it. Ask your doctor or nurse if you have any questions about your medicines, or speak to our Specialist Nurses.

Counselling

Studies suggest there is a link between CPPS and how you’re feeling, so your doctor might refer you to a counsellor or psychologist. They are trained to listen and can help you understand your feelings and find ways to deal with them. Some men find this helpful.

In particular, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can help men find ways to deal with prostatitis. CBT focuses on your thoughts, beliefs and attitudes and how these can affect what you do and how you feel. It involves talking with a therapist who will help you come up with practical ways to change any patterns of behaviour or ways of thinking that may be causing you problems.

You can refer yourself for counselling on the NHS, or you could see a private counsellor. To find out more, visit the NHS website or contact the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy.

There’s been a link between my flare-ups and times of stress or anxiety. CBT certainly helped me, used alongside medication.

Exercises and physical activity

If your doctor thinks your CPPS may be caused by problems with your pelvic floor muscles, they may refer you to a physiotherapist. A physiotherapist helps people to reduce pain through exercises or physical activity. The physiotherapist might show you breathing and relaxation techniques, or massage tender areas of your pelvic floor muscles (known as trigger points).

They might also teach you how to do pelvic floor muscle exercises. The pelvic floor muscles support the bladder and bowel, and help control when you urinate. Doing pelvic floor muscle exercises and stretches can help strengthen the muscles, which may help with urinary symptoms.

Some research has shown that doing regular physical activity can help to prevent CPPS symptoms. Your GP may also be able to refer you to a local exercise programme, or you could join a community walking group. Remember to pace yourself and only do what is comfortable for you.

Treatment for pain

If pain-relieving medicines aren’t helping, your doctor may refer you to a pain clinic. Pain clinics have teams of health professionals who specialise in treating pain and can carry out further assessments and offer a variety of treatments.

Some men have found the following treatments helpful.

- Prostate massage. The doctor massages your prostate through the wall of the back passage (rectum). They will slide their finger gently into your back passage, using gloves and gel to make it more comfortable. If your prostate is tender or painful this might be done under general anaesthetic in hospital so you will be asleep and won’t feel anything. There is no strong scientific evidence for using prostate massage.

- Anti-depressants. If your prostatitis affects your mood and you become very low, depressed or anxious, your doctor might suggest you try taking anti-depressant tablets or refer you to a counsellor. Joining a support group and talking to other people with prostatitis can also help your mood.

- Treatments for sexual problems. If your prostatitis is causing sexual problems such as difficulty getting or keeping an erection, speak to your doctor or nurse. There is support available and things to try that can work well. For example, your doctor can prescribe medicines such as sildenafil (generic sildenafil or Viagra®) or tadalafil (generic tadalafil or Cialis®).

- Surgery. Very occasionally, surgery may be an option. It usually involves removing all or part of the prostate. It isn’t done very often because there’s a chance it may make symptoms worse and cause a number of side effects.

Acute bacterial prostatitis

How is it treated?

Acute bacterial prostatitis is treated with antibiotics. You might get antibiotic tablets to take at home. These should treat the infection quite quickly. You’ll usually take antibiotics for up to four weeks. If the infection is more severe or the antibiotic tablets don’t work well, you may need to take antibiotics for longer. Make sure you finish the course of antibiotics – if you don’t take all the tablets, the infection could come back.

You might also need to spend time in hospital so you can have antibiotics through a drip. A liquid containing antibiotics is passed through a thin tube into a vein, usually in your arm. Once the infection has cleared up, you might get antibiotic tablets to take at home for about two to four weeks.

If acute bacterial prostatitis isn’t treated straight away, you might develop a prostate abscess, where pus builds up inside the prostate. This can be serious and you may need surgery to drain the abscess, as well as antibiotics.

During treatment in hospital or at home, make sure you get plenty of rest and drink enough liquid (six to eight glasses of water a day). Avoid or cut down on fizzy drinks, artificial sweeteners, alcohol and drinks that contain caffeine (tea, coffee and cola), as these can irritate your bladder and make some urinary problems worse. Your doctor may also give you pain-relieving medicines if you need them, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

How is it treated?

Your doctor will give you antibiotic tablets. You’ll need to take these for at least four to six weeks.

If you still have symptoms after you finish the treatment, your doctor may do another urine test to see if the infection has gone.

If the antibiotics don’t get rid of all the bacteria, your symptoms could come back. If this happens, you’ll need more antibiotics.

If the antibiotics do get rid of the infection but you still have symptoms, you might need more tests to find out why. You might be offered another type of medicine, called an alpha-blocker. Some men find that taking alpha-blockers together with antibiotics can help to improve urinary symptoms, such as a weak or slow flow. If you have a lot of discomfort or pain, you may also need to take pain-relieving medicines. Your doctor can recommend ones that are suitable for you.

If your doctor is sure that the infection is chronic (long-lasting), you might be offered a prostate massage to help relieve pain.

Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis

How is it treated?

Because it doesn’t cause symptoms, asymptomatic prostatitis doesn’t usually need any treatment. But you might get a course of antibiotics if:

- you have high levels of a protein called prostate specific antigen (PSA) in your blood, or

- you have high levels of white blood cells in your urine or semen, as this is a sign that you have an infection or inflammation in your body.

If you’re prescribed antibiotics your doctor will tell you how long to take the antibiotics for, but it’s usually around four to six weeks. In most cases, your PSA level will return to normal four to six weeks after you finish your antibiotics.

Living with chronic prostatitis

Long-term prostatitis can be a very difficult condition to live with. The pain or discomfort can make it difficult to carry out everyday tasks, and you might have no warning before having a flare-up.

Travelling long distances or sitting in meetings when you don’t know when you’ll be able to reach a toilet can be worrying, especially if you need to go a lot. And it could be uncomfortable to sit for a long time.

If you’re living with prostatitis it’s natural to feel frustrated. Some men feel that other people don’t understand their symptoms, making them feel alone. Some men even find that living with prostatitis and its symptoms makes them feel depressed or anxious.

Feeling depressed or anxious could actually make your prostatitis symptoms worse. If you feel depressed or anxious, speak to your doctor or nurse. There are things that can help. Sometimes just talking to someone about the way you feel can make things feel better.

If your prostatitis symptoms don’t improve with the treatment offered by your GP, ask them to refer you to a doctor who specialises in managing prostatitis. Your GP may also be able to refer you to a psychologist or counsellor, or you could join a support group. Talking to other people who understand what you’re going through can be helpful.

Speak to your GP about making an action plan so that you know what to do when you have a flare-up. This will help to make sure you can get treatment quickly and get a referral to a specialist if you need it.

This section is about managing long-term prostatitis. If you think you may have acute bacterial prostatitis, speak to your doctor as it can be a serious infection that may need treating in hospital.

Managing pain

If you’re having problems with pain, speak to your doctor. They might prescribe pain-relieving medicines that can help. If these don’t work, ask your doctor to refer you to a pain clinic.

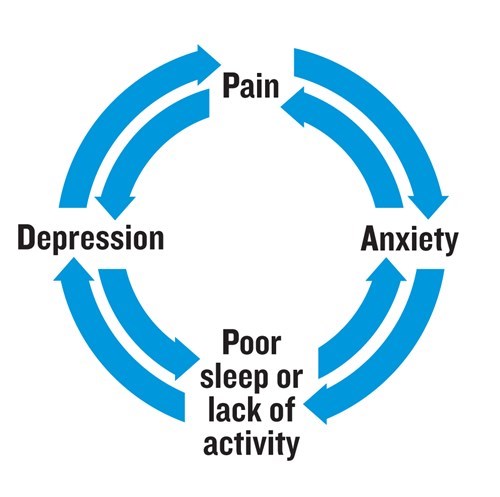

Pain can sometimes make you feel anxious and not want to do anything. But not being active can make you feel down and may actually increase your pain. This is called the pain cycle (see below).

There’s also some research to suggest that how you feel about pain can affect how much pain you feel. So people who think a lot about their pain, or feel there’s nothing they can do to reduce it, can have worse levels of pain. But there are ways to help you manage your pain.

What can I do to help manage pain?

You might find some of the following ideas helpful. They may help you feel more comfortable and more in control of your pain.

- Find ways to relax. Feeling stressed or anxious can cause a flare-up or make symptoms worse. If this is a problem for you, try things to help you relax and feel more in control. You could try relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or meditation, taking a warm bath, or listening to music.

- Distract yourself. Do something to take your mind off the pain, such as listening to music, reading, watching television or chatting with someone. This may sound simple, but it really can help.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). Some people find using a TENS machine helps to relieve pain. A TENS machine uses mild electrical currents that target areas of the body where there is pain. But there isn’t much strong evidence to say it works. Talk to your GP or a pharmacist to find out more about using a TENS machine and how you can get one.

- Pace yourself. Try planning your day by setting goals and include frequent rest breaks. Writing down your goals and prioritising tasks is a good way to stay motivated.

- Sit comfortably. If you need to sit for long periods, for example if you work in an office or do lots of driving, try using a soft or inflatable cushion during a flare-up to reduce the pressure. Change your position regularly to stay as comfortable as possible – you could try standing up and walking around every 30 minutes.

- Get active. Exercise can help some men feel better and reduce symptoms, including pain. This includes brisk walking, jogging or running, or playing sports like football – anything that makes your heart beat faster. Speak to your doctor before you start exercise.

- Stretching. Some men find that doing regular gentle stretching exercises can help them feel better and reduce symptoms. A physiotherapist can show you how to do stretching exercises, or you could try joining a yoga class.

- Try to get plenty of sleep. Talk to your doctor or nurse if something is getting in the way of your sleep. This could be anything from urinary problems to worries that are keeping you awake.

Make some lifestyle changes

There are a number of things you can try that other men have found helpful. You might want to plan your day more, to allow for things like toilet trips. Trying different things can help you feel more in control, and that you are actively doing something to improve your health. If one thing doesn’t work, try something else. Here are some suggestions.

- Watch what you drink. Drink plenty of fluids – about six to eight glasses of water a day. And cut down on fizzy drinks, artificial sweeteners, alcohol and drinks that contain caffeine (tea, coffee and cola) as these can irritate the bladder and make some urinary problems worse.

- Watch what you eat. Some foods may make your symptoms worse. Try to work out what these are so you can avoid them. There’s some evidence that spicy foods can make the symptoms of CPPS worse.

- Avoid cycling. It’s a good idea to avoid activities that put pressure on the area between your back passage and testicles (perineum), such as cycling. They can make symptoms worse. If you want to keep cycling, you could try using a different saddle, such as one made from gel.

- Keep a diary. This can help you spot things that make your symptoms worse, and can be a useful way of showing your doctor what you’re experiencing. Record things like food, drink, exercise, how stressed you feel and your symptoms.

Some men also find that ejaculating regularly helps with their symptoms as it empties some of the fluid from their prostate – although there isn’t much evidence for this and some men may find that the pain gets worse.

For me, the key to managing my prostatitis is being able to recognise the symptoms. Having a treatment plan helps me deal with flare-ups.

Can complementary therapies help?

Many men find complementary therapies help them deal with their symptoms and the day-to-day impact of their prostatitis, helping them feel more in control. Some men find they feel more relaxed and better about themselves and their treatment.

Complementary therapies are usually used alongside medical treatments, rather than instead of them. Some complementary therapies have side effects and some may interfere with your prostatitis treatment. So tell your doctor or nurse about any complementary therapies you’re using or thinking of trying.

You should also tell your complementary therapist about your prostatitis and any treatments you’re having, as this can affect what therapies are safe and suitable for you.

Some GPs and hospitals offer complementary therapies. But if you want to find a therapist yourself, make sure they are properly qualified and belong to a professional body. The Complementary and Natural Healthcare Council have advice about finding a therapist.

The following are examples of complementary therapies that some men use.

- Acupuncture. This involves inserting very thin needles just below the skin at specific points on the body. Some research suggests it may help to relieve pain. Electro-acupuncture may also help relieve pain. This is where small electrical currents are passed through the needles. Ask your doctor if it is available on the NHS in your area. Or you can find a private acupuncturist through the British Acupuncture Council.

- Massage, reflexology, aromatherapy or hypnotherapy. Some people with pain caused by other conditions find that these therapies help them feel better about themselves and their treatment. They might also help to relieve stress, making you feel more relaxed.

- Meditation and relaxation. Some people find that doing meditation or relaxation exercises can help them feel less anxious. One way of meditating, called mindfulness, is about staying focused on what is happening in the present moment. Sitting quietly each day and focusing on your breathing is a good way to be mindful. Other people may prefer writing, drawing, or listening to gentle music. This is often a good way to take your mind off things.

- Supplements or herbal remedies. Researchers are currently looking into several plant extracts. Some men find they help to ease pain or urinary symptoms. A small amount of research suggests that quercetin and rye grass pollen may be helpful. Some men find that the plant extract saw palmetto helps, although there’s no scientific evidence for it. If you are thinking about using supplements or herbal remedies, speak to your doctor or nurse. Some may have side effects or interfere with some treatments for prostatitis.

Be very careful when buying herbal remedies over the internet. Many are made outside the UK and may not be high-quality. Many companies make claims that aren’t based on proper research. There may be no real evidence that their products work, and some may even be harmful. Remember that even if a product is ‘natural’, this doesn’t mean it is safe. For more information about using herbal remedies safely visit the MHRA website.

Getting support

As well as trying things to help yourself, some men find getting support is useful.

Your medical team

It may be useful to speak to your GP, doctor or nurse at the hospital, or someone else in your medical team. They can help you understand your diagnosis, treatment and side effects. They can also listen to your concerns, and put you in touch with other people who can help.

Our Specialist Nurses

Our Specialist Nurses can help explain your diagnosis and treatment options. They have time to listen, in confidence, to any concerns you or those close to you have about living with prostatitis. Call our Specialist Nurses on 0800 074 8383, or chat online.

Our online community

Our online community is a place to talk about whatever’s on your mind – your questions, your ups and your downs. Anyone can ask a question or share their experience of living with prostatitis.

What research is being done?

Researchers are trying to find out more about prostatitis so that they can develop better treatments.

They’re looking into the causes of CPPS and why it affects men differently. This includes looking at the genes involved. A better understanding of the causes will mean that, in the future, treatments can be tailored to suit each man.

They’re also looking into different treatments. These include a number of medicines, botox, surgery, and using small electrical currents to reduce pain.

Another area of research is looking at ways to help men live with CPPS, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and ways men can take more control themselves – such as with diet and supplements.

At the moment, most of the research is happening in other countries, but if you’re interested in taking part in a clinical trial, mention this to your doctor. There might be trials you can join in the future.

References

Last updated: November 2022 | To be reviewed: March 2024

- Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Morey A, Chavez N, Chan CA. Stress Induced Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Responses and Disturbances in Psychological Profiles in Men With Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. J Urol. 2009 Nov;182(5):2319–24.

- Anderson RU, Wise D, Nathanson BH. Chronic Prostatitis and/or Chronic Pelvic Pain as a Psychoneuromuscular Disorder—A Meta-analysis. Urology. 2018 Oct 1;120:23–9.

- BMJ Best Practice. Acute prostatitis- Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 31]. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/172/pdf/172/Acute%20prostatitis.pdf

- Boehm K, Valdivieso R, Meskawi M, Larcher A, Schiffmann J, Sun M, et al. Prostatitis, other genitourinary infections and prostate cancer: results from a population-based case–control study. World J Urol. 2016 Mar 1;34(3):425–30.

- Bonkat G, Bartoletti R, Bruyère F, Cai T, Geerlings SE, Koves B, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 25]. Available from: https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Urological-Infections-2022.pdf

- Cai T, Verze P, La Rocca R, Anceschi U, De Nunzio C, Mirone V. The role of flower pollen extract in managing patients affected by chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a comprehensive analysis of all published clinical trials. BMC Urol. 2017 Apr 21;17(1):32.

- Cheng I, Witte JS, Jacobsen SJ, Haque R, Quinn VP, Quesenberry CP, et al. Prostatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and Prostate Cancer: The California Men’s Health Study. PLoS ONE [Internet]. 2010 Jan 15 [cited 2019 Jul 11];5(1). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2806913/

- Chung S-D, Lin H-C. Association between Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome and Anxiety Disorder: A Population-Based Study. Thumbikat P, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013 May 15;8(5):e64630.

- Coker TJ, Dierfeldt DM. Acute Bacterial Prostatitis: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Jan 15;93(2):114–20.

- Doat S, Marous M, Rebillard X, Trétarre B, Lamy P-J, Soares P, et al. Prostatitis, other genitourinary infections and prostate cancer risk: Influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs? Results from the EPICAP study. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(7):1644–51.

- Engeler D, Baranowski AP, Berghmans B, Birch J, Borovicka J, Dinis-Oliveira P, et al. EAU Guidelines on Chronic Pelvic Pain [Internet]. European Association of Urology; 2022. Available from: https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Chronic-Pelvic-Pain-2022_2022-03-29-084111_kpbq.pdf

- Franco JV, Turk T, Jung JH, Xiao Y-T, Iakhno S, Garrote V, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for treating chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Cochrane Urology Group, editor. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 May 12 [cited 2019 Jan 3]; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD012551.pub3

- Gallo L. Effectiveness of diet, sexual habits and lifestyle modifications on treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014 Sep;17(3):238–45.

- Giubilei G, Mondaini N, Minervini A, Saieva C, Lapini A, Serni S, et al. Physical Activity of Men With Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome Not Satisfied With Conventional Treatments—Could it Represent a Valid Option? The Physical Activity and Male Pelvic Pain Trial: A Double-Blind, Randomized Study. J Urol. 2007 Jan;177(1):159–65.

- Giulianelli R, Pecoraro S, Sepe G, Leonardi R, Gentile BC, Albanesi L, et al. Multicentre study on the efficacy and tolerability of an extract of Serenoa repens in patients with chronic benign prostate conditions associated with inflammation. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2012 Jun;84(2):94–8.

- Gurel B, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Kristal AR, et al. Chronic Inflammation in Benign Prostate Tissue Is Associated with High-Grade Prostate Cancer in the Placebo Arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014 May 1;23(5):847–56.

- Herati AS, Shorter B, Srinivasan AK, Tai J, Seideman C, Lesser M, et al. Effects of foods and beverages on the symptoms of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2013 Dec;82(6):1376–80.

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, Metcalf CA, Morris LK, Robinaugh DJ, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness Meditation for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Effects on Anxiety and Stress Reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013 Aug;74(8):786–92.

- Jiang J, Li J, Yunxia Z, Zhu H, Liu J, Pumill C. The Role of Prostatitis in Prostate Cancer: Meta-Analysis. Gakis G, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013 Dec 31;8(12):e85179.

- Lee DS, Choe H-S, Kim HY, Kim SW, Bae SR, Yoon BI, et al. Acute bacterial prostatitis and abscess formation. BMC Urol [Internet]. 2016 Jul 7 [cited 2019 May 29];16. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4936164/

- Lee S-H, Lee B-C. Electroacupuncture Relieves Pain in Men With Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: Three-arm Randomized Trial. Urology. 2009 May;73(5):1036–41.

- Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, FOWLER JR FJ, Nickel JC, CALHOUN EA, Pontari MA, et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. J Urol. 1999;162(2):369–375.

- Moore P, Cole F. The pain toolkit. Lond UK NHS [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2015 Sep 1]; Available from: https://www.paintoolkit.org/persistent-pain/pain-cycle

- Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 6;(7):CD008242.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Prostatitis (acute): antimicrobial prescribing. NICE guideline 110 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 3]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng110

- Nickel JC. Prostatitis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011 Oct;5(5):306–15.

- Perletti G, Monti E, Magri V, Cai T, Cleves A, Trinchieri A, et al. The association between prostatitis and prostate cancer. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Ital Urol E Androl. 2017 Dec 31;89(4):259–65.

- Qin Z, Wu J, Zhou J, Liu Z. Systematic Review of Acupuncture for Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) [Internet]. 2016 Mar 18 [cited 2019 Jan 3];95(11). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4839929/

- Qin Z, Zang Z, Zhou K, Wu J, Zhou J, Kwong JSW, et al. Acupuncture for Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Randomized, Sham Acupuncture Controlled Trial. J Urol. 2018 Oct 1;200(4):815–22.

- Rees J, Abrahams M, Doble A, Cooper A, the Prostatitis Expert Reference Group (PERG). Diagnosis and treatment of chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a consensus guideline. BJU Int. 2015 Oct;116(4):509–25.

- Riegel B, Bruenahl CA, Ahyai S, Bingel U, Fisch M, Löwe B. Assessing psychological factors, social aspects and psychiatric co-morbidity associated with Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS) in men — A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2014 Nov;77(5):333–50.

- Shoskes DA, Nickel JC. Quercetin for Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Urol Clin North Am. 2011 Aug;38(3):279–84.

- Strauss AC, Dimitrakov JD. New treatments for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2010 Mar;7(3):127–35.

- SUN Z, BAO Y. Eliminating sedimentation for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Exp Ther Med. 2013 May;5(5):1339–44.

- Thakkinstian A, Attia J, Anothaisintawee T, Nickel JC. α-blockers, antibiotics and anti-inflammatories have a role in the management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2012 Oct;110(7):1014–22.

- Zhang M-F, Wen Y-S, Liu W-Y, Peng L-F, Wu X-D, Liu Q-W. Effectiveness of Mindfulness-based Therapy for Reducing Anxiety and Depression in Patients With Cancer: A Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015 Nov;94(45):e0897-0890.

- Zhang R, Chomistek AK, Dimitrakoff JD, Giovannucci EL, Willett WC, Rosner BA, et al. Physical Activity and Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 Apr;47(4):757–64.